When my baby was born, I started thinking about all kinds of grown up things I never thought about before.

One of them was buying life insurance.

There’s a lot of different types of life insurance products: term life, whole life, return of premium, universal, universal index, variable, variable universal, survivorship, mortgage protection, final expense. I’m sure there’s more. It can make your head spin.

Luckily, there’s a lot of blog posts out there explaining the nuances between these different products. So I won’t focus on that here.

But I also noticed most blog posts are hand-wavy when it comes to advising you on how to think about how much life insurance you need.

They’ll say something like: “Add up your mortgage, kids’ college expenses, credit card debt, student loans, other major debts, and annual spend – that’s a rough estimate of how much insurance you need.”

The problem is: you shouldn’t just add these up because they all behave differently. Some decrease, others fluctuate, others increase.

What the blog posts are missing is a guide to help you calculate – quantitatively and precisely – how these expenses change over time.

Knowing how to do this will give you a far clearer picture of exactly how much insurance you actually need. So in this article, I’ll share my framework for how to do this exact calculation.

I’ll also show you how to calculate whether regular term life vs. return of premium insurance is more cost-effective.

First, how to think about life insurance in general

The basic idea of life insurance is: pay the insurer a little each month, and if you die the insurer pays your beneficiaries a big death benefit. Most people won’t die during their life insurance contract, so they’ll get nothing.

Well, not nothing. They get peace of mind their dependents won’t go through severe financial stress (on top of emotional stress) if you die. This is especially reassuring if you’re the sole breadwinner.

The bigger your obligations, and the more dependents you have, the more valuable life insurance is. Think about if you had a jumbo mortgage, student loans, car payments, three pre-college kids, a stay-at-home spouse.

Generally, the younger you are, the more valuable life insurance is, and therefore the more risky it is to ignore it, because the less likely it is you’re financially independent. At the same time, it’s less risky to the insurance company because young people are generally healthier.

The older you are, the riskier you are to the insurer, but also the less valuable life insurance is to you because you’re more likely to be financially independent, debt-free, and self-insured. So as you get older, you need life insurance less. You’ll have paid off your mortgage, sent your kids to college, built a nest egg. Unless you have a special situation (e.g., dependent with lifetime special needs), at some point you probably won’t need life insurance anymore.

That’s why the most basic type of life insurance, term life, expires after a set period, usually 10, 15, 20, or 30 years.

How to calculate exactly how much life insurance you need

Most blog posts, in a hand-wavy way, suggest that you add up all your mortgages, student loans, and other debts, along with your kids’ expected college costs and maybe your family spending to “ballpark” how much insurance to buy.

This shortcut is imprecise and inaccurate. Your debts and major expenses are not static. Debts go down over time. Expenses go up with (at least) inflation.

Your life insurance should mirror and adjust accordingly, because you’ll be paying your policy for many years. So when you calculate how much insurance you need, take these movements into account.

You may realize after doing an analysis that it doesn’t make sense to buy one single big policy. It may be cheaper to “ladder” two or more policies together to lower your overall premiums while still fulfilling your coverage needs.

For example, say you’re 38 and you have a mortgage with $400k left on it, and you expect to pay it off in 17 years. Say you also have two kids, 3 and 8, for whom you want to save for college. College today costs upward of $320+ at many private universities and is growing ~5% annually.

Here, you have 3 major milestones. One is 17 years from now when you pay off your mortgage. Another is 15 years from now when your younger kid heads off to college. The third is 10 years from now when your older kid goes to college.

As of right this second, you might think your life insurance needs are: $400k + $320k + $320k. Total $1,040k. (Round it up to an even $1.1 million for simplicity.)

Now, if I look on a life insurance search engine (Google around to find one), I can see that a rough ballpark quote for appropriate coverage for 15 years costs $37-$85 per month.

For 20 years it costs $52-$111 per month.

Note: for running these quotes, I assumed you’re a 38-year-old male, 5 foot 8 inch, 150 pounds, in excellent health (no smoking, diabetes, heart disease history, etc).

But your $400k mortgage will decrease over time. In 8 years, it will be roughly half the current amount. Meanwhile, the $640k in college expenses for both your kids is in today’s dollars. 10 or 15 years from now, it’ll be significantly more than $640k simply due to inflation.

So, in a way, your declining mortgage balance is offsetting your increasing college expense requirements. But is your overall life insurance need increasing or decreasing? Not clear without doing some math. Are you sure buying a $1.1 million policy is the right choice?

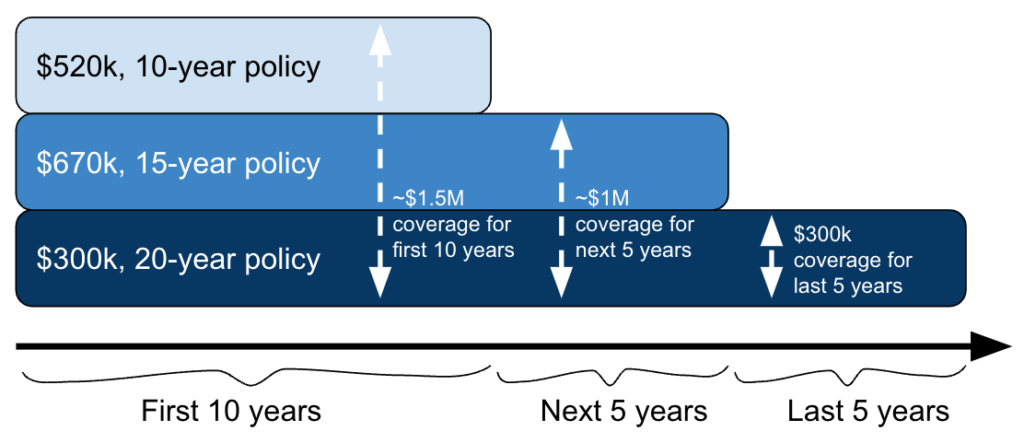

Even if $1.1 million is roughly correct (which it isn’t in this example’s math), instead of buying one single $1.1 million policy for 15 or 20 years, it might be cheaper to buy, say, a 20-year policy for $300k (mortgage), a 15-year policy for $670k (younger kid college, adjusted for inflation), and a 10-year policy for $520k (older kid college, adjusted for inflation).

Of course, dealing with 3 separate policies is more complicated, but it could translate into real savings every single month for a decade or two, which might make it worthwhile.

The point is, do the math and research different policies and insurers to actually know which path is cheaper. Spending a little time to do this calculation right will give you confidence you’re making the best choice for your needs.

Here’s how to do it:

1. Calculate your mortgage amortization. Your mortgage is probably your biggest financial obligation so it will occupy a large portion of your life insurance needs. Luckily, it’s easy to calculate, to the penny, exactly how your mortgage will decline over time.

I won’t bore you with the formula to do this (get my life insurance calculator spreadsheet tool to do it automatically), but the point is you can forecast exactly how your mortgage will decline each year until it’s paid off. This is called an amortization schedule.

Create one of these schedules for each mortgage you have and see what you’ll still owe at key points in the future, e.g., 10, 15, 20, 30 years from now. These are the most common durations for life insurance contracts.

2. Calculate your other debts. Just like your mortgages, you should calculate amortization schedules for your other major debts. Student loans, auto loans, etc.

If your other debts have fixed payoff schedules and fixed interest rates, you can use the same formulas and spreadsheet used for mortgages to calculate the exact payoffs for your other debts.

Even if the interest rates or payoff schedules are variable or complicated (e.g., linked to your salary level), you can still use simple amortization math to estimate the payoff schedule. (It’ll be close enough.) Again, my life insurance calculator spreadsheet can help here.

3. Calculate major expected costs, adjust for inflation. Beyond estimating your debts, you should also forecast major expenses.

While you cannot predict sudden costs like emergency medical expenses, you can predict major things like paying for your kids’ college. It’s worth thinking about those and forecasting how they will grow over the years.

If you are a sole breadwinner and your family’s living expenses are high, you might want to factor in some or all of those living expenses, too.

My family spends pretty frugally, and my spouse works full-time, so I’m not worried about them running into hardship for living expenses should I die. By contrast, saving for our kids’ college will be materially harder if I die because the family would suddenly lose a lot of income. So, in my case, I factored in future college expenses into my life insurance calculation.

Whatever expenses you predict, forecast what they’ll be at the same key points in the future, e.g., 10, 15, 20, 30 years from now. Again, these numbers are the most common life insurance terms.

4. Analyze where the sharp declines are, then compare prices for single big policies vs. smaller laddered policies.

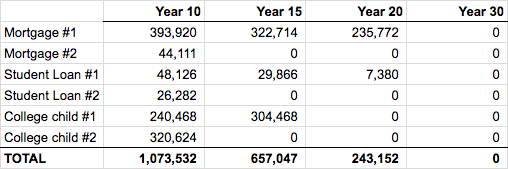

Now that you know how your debts will decline and how your key expenses will “inflate” in the future, just do simple math to add up the amounts at 10, 15, 20, 30 years.

I suggest building a little table like this so you can see everything at a glance:

Now you have clear data on how your life insurance needs will change over time.

Now it’s time to go shopping for policies. Go to your insurance agent or search online to get quotes.

Look at the cost of buying a single term policy vs. two or more policies of different term lengths that ladder together (coverage will decline over time as shorter policies expire).

You may find that with laddered policies, you still fulfill your coverage needs (e.g., mortgage, college expenses) but pay lower premiums.

YMMV so be sure to do the math yourself to verify which path is cheaper. Sometimes one single policy is cheaper, other times laddered policies are cheaper.

Which is a better deal: term life vs. return of premium?

Even after you know exactly how much life insurance to buy, there are a couple different options for term life policies.

One type of term life policy is called “return of premium” insurance. The way it works is, after your term expires, if you didn’t die the insurance company will refund you back all your premiums. (If you die, there’s no refund but your beneficiaries get the death benefit.)

Why does the insurance company do this? Because they know some customers feel jipped when their policy expires and they didn’t die. They think, “Hey, I paid good money and I didn’t get anything!”

Which is wrong. They got peace of mind for all those years that their family would be taken care of if they died. It’s not really the insurer’s fault they didn’t die.

Either way, some customers don’t like the idea of paying money for “nothing,” so insurance companies created this new product called “return of premium” to make customers “feel better” when their policy expired.

It feels good getting your money back, right? Kind of like getting a nice big tax refund at the end of the year.

But what’s the catch?

Two things. One, the premiums for this type of insurance are way more expensive. Double the cost or more. Two, since money declines in value over time due to inflation, you’re actually getting back less money when your premiums are refunded because you get no adjustment for inflation.

So how do you know whether “return of premium” is a good deal? And how do you determine whether it’s right for you?

First, I’ll assume you already decided whole life insurance isn’t right for you (given it’s not right for 98% of people because of its inferior returns vs. other asset classes, it costing ~10x more than term life, plus all the rules and restrictions for using it).

The basic idea behind determining whether plain vanilla term vs. return of premium is better is to compare what you pay for plain vanilla vs. what you pay for return of premium.

But wait, you get your premiums back with return of premium, so doesn’t it cost zero? No. You pay with dollars today but get back “less valuable” dollars in the future, so what you “pay” is the difference between the two.

To know how much less valuable those future dollars are, you have to know the rate of return.

By rate of return, I mean: you have to know what investment return you must beat for that future “return of premium” refund to NOT be worth it.

That’s because there’s this saying in the insurance industry: “pay term, invest the difference.” It means that, because plain vanilla term life is the cheapest type of life insurance, you should just buy that and invest the “savings” from skipping the more expensive options.

Since return of premium is more expensive, if you can “pay term and invest the difference” at a high enough rate of return, then you won’t need your premiums to be returned at the end and you can still come out ahead. In other words, it could be better to forgo the premium refund if your investment returns elsewhere are high enough.

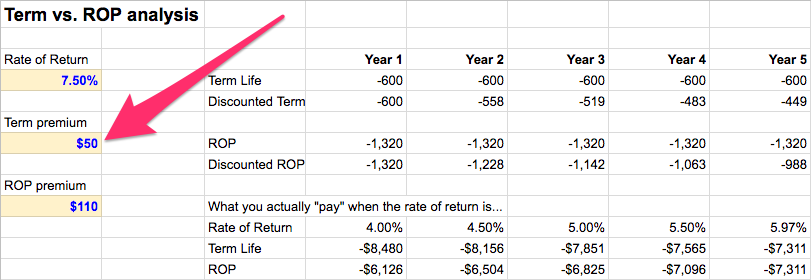

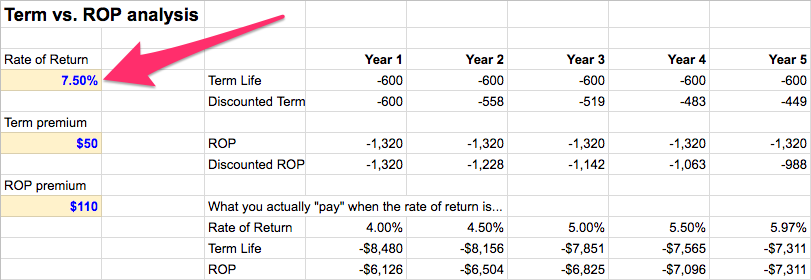

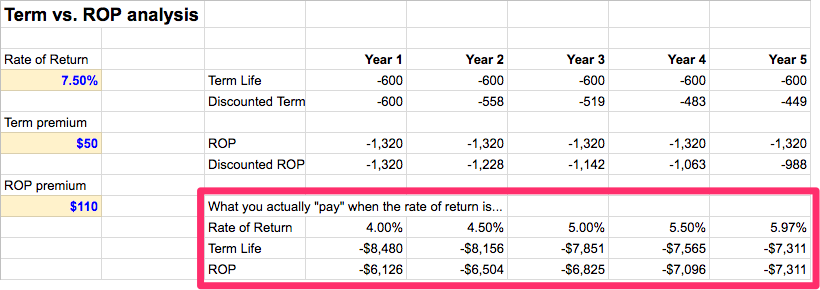

My life insurance spreadsheet will help you calculate (and visualize) this in a jiffy:

1. Enter the premium cost for plain vanilla term life.

2. Enter the premium cost for return of premium. (If you’re not using my spreadsheet, remember to “offset” the refund of premiums at the end of the policy; we have to assume you survive the policy for this analysis.)

3. Enter your personal investment rate of return. This is the annual rate of return you believe you can get, on average, over the course of your policy (e.g., 20 years). The spreadsheet will automatically calculate how much less valuable dollars in the future are worth based on the rate of return you enter.

4. Now just add up the dollars for each type of insurance and compare them. My spreadsheet helps you see a range of rates of return and visualize the “break even” point where the two types of insurance are economically equivalent, i.e., what rate of return would make you indifferent to either option.

Since higher rates of return make term life more attractive, the “break even” point is the rate of return you have to beat in your personal investments to make term life more economical than return of premium.

Of course, all this assumes you actually DO invest the difference. If you just put it in a zero interest bank account, then buying plain vanilla term life never makes sense; you might as well buy return of premium because at least you’ll get a non-zero rate of return there!

Two simple but important insights emerge from this analysis.

One: the more expensive return of premium is, the less attractive, because then even a very low rate of return will cause plain vanilla term life to be superior.

And vice versa: the cheaper it is, the more attractive…which makes sense because, in the most extreme case, if return of premium was the exact same price as plain vanilla, then everyone on earth would buy it and no one would buy plain vanilla. There’d be no risk – and no rate of return would make plain vanilla superior.

Two: the higher your personal investment rate of return, the less attractive return of premium is. A mental shortcut: if return of premium is double the cost of plain vanilla term life, then the investment return you have to beat is ~6-7% for term life to be superior.

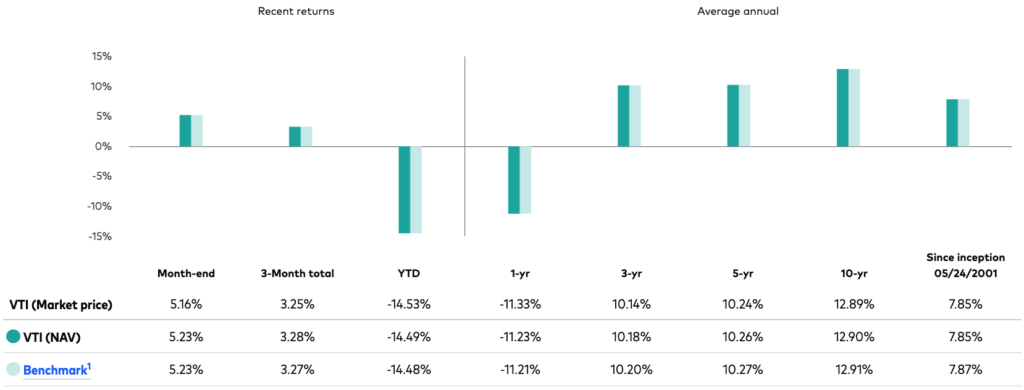

And since you can at least match the overall market return (for no effort) by simply buying cheap index funds like Vanguard’s VTI, you can get a pretty good idea of the minimum investment return you can expect over different time periods:

Note: VTI has only been around since 5/2001, so there is no performance history before that.

(Of course, you’ll have to consider things like market volatility and timing which can heavily influence short-term returns. But over long periods these things generally smooth out.)

Knowing these two pieces of info – the return you need to beat vs. the minimum return you can expect – is the key insight that will help you decide whether plain vanilla term vs. return of premium is the better deal.

Now it’s your turn

Hopefully you learned something in this post.

First, I showed you step by step the “right way” to calculate the exact amount of life insurance you need. Precision will give you confidence you’re making the right life insurance decision for your family.

Second, I showed you how to calculate whether plain vanilla term life vs. return of premium is a better deal. Figuring out how your personal rate of return compares to the “break even” rate of return will clarify this decision for you.

The best part is, we did this in a very quantitative way with very little guesswork.

With this framework (and our life insurance spreadsheet tool), you’ll no longer have to worry about incorrectly estimating your life insurance needs or making a long-term insurance commitment in a hand-wavy way. You have all the tools you need to buy the right policy cost-efficiently.

Use this info to get the most bang for buck when you buy life insurance!

If you’re thinking about life insurance, you should also consider estate planning strategies, most importantly setting up a revocable living trust. Check out my post on how to set up a revocable living trust (with sample trust document).

Discussion: How do you determine how much life insurance you need? Any special tips you use to evaluate which type of insurance product to buy? Leave a comment below!

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for this article, very insightful. I’ve also enjoyed the spreadsheet – super helpful!

Is it worth having life insurance if your are expecting children in the next 3-5 years? Or is it better to wait until the children come? I have a life policy of 2 years salary through my work, but not enough to cover the mortgage that would be due if I were to pass away. (Also, getting married in 6 months)

Thanks,

David

Hey David, thanks for your comment and glad the post is useful.

It’s really a personal decision. On the one hand, 5 years is a long time to pay for life insurance if you don’t have dependents (my opinion). If you die childless (knock on wood), the value of life insurance is presumably less without dependents (assuming your fiancee/wife is able to work and doesn’t depend on your income). It becomes a lot more valuable once you have people depending on you (who cannot work). On the other hand, your premiums will be lower when you’re younger. Be aware that some insurers offer lower premiums after you’re married (on the theory that you’re less likely to do risky/dangerous things vs. as a bachelor).