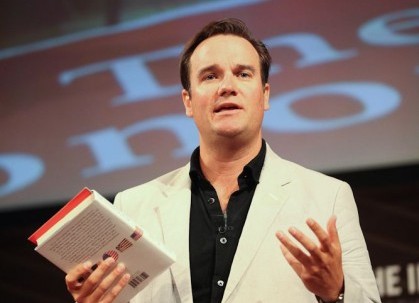

This interview is with Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries and co-author of True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership. He is a member of GE’s Innovation Advisory Panel and a cofounder and director of Fuse Corps, a social venture partnership with McKinsey & Company that places promising young leaders in year-long projects with mayors and governors across America to tackle critical public policy challenges facing our nation. (Download the audio recording of this interview.)

This interview is with Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries and co-author of True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership. He is a member of GE’s Innovation Advisory Panel and a cofounder and director of Fuse Corps, a social venture partnership with McKinsey & Company that places promising young leaders in year-long projects with mayors and governors across America to tackle critical public policy challenges facing our nation. (Download the audio recording of this interview.)

Career path:

- Bowdoin undergrad

- Deloitte Consulting

- Summit Partners

- Stanford MBA

- Wrote “Little Bets”

Q. Tell me about your background.

A. I’m 36. My academic background is that I’ve been a student of the humanities, a student of business, an MBA. I basically am a lifelong learner. I try to learn a little bit from everyone I speak with. So that’s who I am.

Q. In your book with Bill George, True North, you talk about how personal stories and struggles form one’s leadership style.

Many leaders experience what you describe as a “crucible,” or challenging period in life that deeply tests them and transforms their understanding of leadership.

How has your own career path unfolded into your current role as an entrepreneur, author, and lecturer on design thinking? What were your “crucible” moments?

A. Great question. My career path has two parts. One part was when I was younger. I wasn’t a very good student in the early grades. I got kicked out of my second grade class for wanting to go out and play too much.

But I ended up getting really interested in achievement starting in junior high or 6th grade. My parents really emphasized the importance of achievement, so from then on, I really focused on external achievement because that’s what, I guess, I was supposed to do.

I also enjoyed the process of having a goal and achieving it, whether it was on the athletic fields, where I was the captain of teams, or elsewhere.

I got to Bowdoin College, and I was lucky to get admitted to Bowdoin College because I didn’t do very well on my SATs, but they let me in anyway.

When I got there, I was first interested in trying to become a better writer, because I just really didn’t know how to write when I got to college. I’d gone to a pretty small rural high school in Northern California, and I worked really hard to catch up with the kids who were from prep schools and who were a little bit better prepared than I was.

Fortunately, Bowdoin had an environment that was really conducive to studying the humanities. I took classes across sociology and economics. Government was my major; history was my minor. I really passionately studied history and Civil War history in particular and a lot of American government. I took a strong interest in European history as well. I took classes across the board.

When I graduated, I was not prepared for the business world because I didn’t know how to use Excel. And that was the first assignment I had when I got to Deloitte Consulting. So, for the first year-and-a-half into my career, I just tried to learn the basic skills you need to have to do a job.

So I learned about Excel. I learned about PowerPoint. I learned about all the things you do when you start a job. And that was really helpful because I hadn’t learned any of those skills in school, but I had learned how to think about industries and that was helpful in consulting.

I was only going to stay in consulting for a year-and-a-half. I ended up working on the strategy team. I was an analyst on the strategy team that supported the Deloitte Consulting global strategy, and that was a fascinating experience for me because I got a chance to get exposed to a whole bunch of people who were from different offices of the firm.

And thinking of the progression of my career, I had some interest in business when I was in high school. I got a chance to work at the savings and loan that my scout master Bob Hayden ran, and I really enjoyed that job. So I guess I was interested in business from that age.

Then, when I went to Bowdoin College, I was very involved in extracurricular activities. I was president of my class my junior year, and then I was on a bunch of trustee committees my senior year. I got to know some people there.

This is where I really think the experiences you get, whether they’re in school or after, are so valuable, because I got to know a number of people who were trustees at Bowdoin who I’ve kept in touch with, including a guy by the name of Bob White, who was one of the co-founders of an investment firm, a venture capital and private equity firm, called Bain Capital.

Bain Capital obviously is very well-known today because Mitt Romney was a founder of Bain Capital. In fact, he brought Bob White with him to start the firm with two or three other people. And so, I was able to learn from people like Bob White, who respected me for my point of view when I was a student, and I then aspired to get into venture capital because that’s how I perceived things to get done.

But all this is very extrinsic, very external. I’m really not thinking of anything besides that I’m identifying with my achievements. So I’ll summarize in a very concrete way what I learned about achievement in the first part of my career, and that is, our parents teach us about the importance of doing well in things, whether it’s grades or athletic achievement or what-have-you. That’s a really strong cultural norm in the United States, and around the world.

I did that to no end, relentlessly, until I was about 30 years old. Along the way, I was definitely following curiosity. I was getting to know interesting people. I was following those types of crumbs to piece together what my career was going to be — and skills. I was building skills. And you begin to feel like there’s a linear progression. I did, at least, when I went from consulting to venture capital.

When I was in venture capital with Summit Partners in Boston, I worked for a great guy, Marty Mannion, who really taught me everything I know about investing. Then I was asked by another partner to go to London to start the London office with this partner, the European office of Summit Partners. So I was interacting with entrepreneurs all across the US and Europe.

Again and again, I just didn’t feel a sense of meaning. I had a great experience in Europe. I felt lucky to be there. I mean, I’m from a small town and it was a progression farther and farther away from home. My girlfriend was French, and that was awesome. It was just a great cultural experience.

But then, I basically hit the wall. That was the first wall I hit. I hit a number of walls. This was when I was about 26 or 27 when I hit the first wall. I just had a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I just had a hard time getting motivated for work. And I had already applied to business school, so I was hopeful I would get in, and fortunately, I got in to Stanford, so that was very lucky.

The people I worked with at Summit were great. The person I went to London with, Scott Collins, and I keep in close touch, relatively close touch. We worked out of a suitcase for two years to try to start up an office there. And now, it’s got 15 people. They’ve got a billion-dollar fund, and so it feels rewarding to look back on it in that way.

But I went to business school to figure out what to do. The first year at Stanford, the time I went, was, in my opinion, soul-crushing. The reason I say that is because there’s no room for creativity in the curriculum at the time. So you’d take classes ranging from operations to microeconomics to statistics, all that stuff.

That’s all very valuable. I had taken a lot of those classes before at Bowdoin, and so I felt it was a bit repetitive. I also felt it was a bit too theoretical for the type of work I was interested in. I mean, coming out of Summit, I really loved entrepreneurs, and working in Europe, I just had so much admiration for the — I hate to use the term — “American entrepreneur,” but just the American style of entrepreneurship.

I just remember feeling like going to Stanford would be a chance to connect with that, and get back close to my family, which was more important.

Anyway, long story short, all that is external. What changed, what flipped, starting in business school, was that I started to get more in touch with my own values and what was important to me. Part of that process was just reacting to things I didn’t like, like the first-year curriculum at Stanford.

I nearly thought about dropping out. They’ve since changed their curriculum, but I thought about dropping out that first year because I was exhausted. So then, at the end of the first year, one of the great things about going to business school, especially at places like Stanford where they have a really strong network, is that they have guest speakers come in like Bill George.

So Bill George, the former CEO of Medtronic, came to speak. He was a really smart guy who was talking about values and leadership, authenticy and authentic leadership. And that really resonated with me. My parents are both very authentic people. I came from a very small town where people are just pretty authentic. So when Bill came, I thought he was a very credible person to speak about this.

I had the chance to meet him briefly afterward with a couple of my classmates. Then he and I kept in touch. We invited him to become a lecturer at Stanford. We got permission from the dean to do that. He said he was fully committed to HBS because that was his alma mater and he was working on developing courses there.

So, a friend of mine, Ryan Frederick, and I said, “Screw this. We’re going to start a class because this is important. We want to talk about this here, and we don’t have classes on leadership here at Stanford.”

That has since changed, too. But at the time, there wasn’t really much offering to think and talk about leadership. That’s kind of a loaded term, but really, it was about how do you take your values and make a difference in the world, make an impact in the business world? So that was a class called “Leadership Perspectives” that we recruited a couple of professors for, Charles O’Reilly and Joel Peterson — they’re both really interesting, insightful people.

Charles is an academic and Joel is a practitioner. And so, we had all kinds of fun developing this class with a group of our classmates over the summer between the two years. And I had interned with a top entrepreneur, Chet Pipkin, that summer in Los Angeles, one of the Summit portfolio companies.

And I just got really into this project. And Bill George and I got to know each other, because we would talk once a week, and he invited Ryan and me out to Colorado with some of his students from HBS. We just had a great time learning and conceptualizing how to piece these classes together.

So we learned a lot from each other. He needed to get insight from younger people. And he and I would talk a lot about conceptual development of ideas. He bounced ideas for a book on authentic leadership, and I had been talking with him so much about this stuff that he said, “You know, would you like to work on that project together?”

And I said, “Wow, yes, that would be amazing. Thank you so much. That sounds like an incredible opportunity, a once-in-a-lifetime experience to meet people and interview people like we’ve been doing for this class at Stanford, Leadership Perspectives.”

So I figured I’d just do that once and then go back and get a job. But what happened was, it was the richest learning experience of my life. I met a lot of people who were really inspiring; I was really inspired by Howard Schultz of Starbucks and Richard Tait, who was the founder of Cranium, and had a really memorable day the day we interviewed them. I think this was back in 2005, and I realized I really wanted to be an entrepreneur that day, because Howard and Richard were both what I consider examples of “artistic” entrepreneurs. And so that felt, to me, like it fit. Inside, there was some voice telling me that. But it would be years before I fully realized how to make it happen.

So this was all, again, part of the transition. The other thing that happened was I realized in this transition phase between extrinsic and more intrinsic motivation that it was really important not only to know my values but to know my interests.

And then that’s really where a problem set in, because we wrote the book, True North, and did all the research and did the book, and Bill and I both felt really proud of the product, and then you’ve got to go out and market the book. You’ve got to go out and do speaking. And that was new for me, so I was really uncomfortable going on a national stage.

I was 30 years old, and I was really quite uncomfortable in my skin at that stage. I now see this with my colleagues at the BLKSHP who are on the national stage for the first time, and it’s interesting to watch, because they go through some of the same things I experienced. And so, long story short, I had to learn a lot about self-awareness before I was really ready to do something like that.

I thought, again, that I’d just go back and get a job, something entrepreneurial. But there were a couple crucibles that happened in that time frame. One was that Bill and I just could not agree on the right role for me for this launch of True North. And so, painful as it was for me to have to sit back and watch from the sidelines after this work of art went out to the world — we were so proud of the work — it was the right thing, because it was Bill’s book and I was lucky to be the junior author on the book. So I needed to learn from that experience about just how to effectively do different stages of promoting an idea or product.

Around the same time, I really got into this whole field of design and design thinking at the Stanford d.school. I just followed my interests, and this is a longer conversation but it was really in that period when I had this conflict with Bill, a very significant, serious conflict. He and I are now cordial and friendly, and I love what he’s doing. I think he’s a terrific thought leader and voice.

But I had to learn about what was important to me first, and I was really interested in this field of design. It was just creativity, and all of a sudden, I got into prototyping and experimenting, acting like an anthropologist and learning all these methods from design, which were really what they used at Apple to develop ideas, for the most part.

It changed the way I thought. It shifted me from being totally in the left brain, totally rational, totally focused on achievement to transitioning toward being in my own body, being in my values, being creative. I never thought of myself as creative before, but I had this amazing mentor and friend, George Kembel, who was a co-founder and the head of the design school, who taught me all this. He was just a great support, too.

So I found that my friendship group started to change, too. I didn’t hang out with Stanford MBAs on the weekend. I started hanging out with ballerinas or entrepreneurs or writers. And the more I spent time with a different group of people, the more it reinforced this more creative approach to life.

But I still was going through a very difficult time to sort through my interests, because I had so many interests. I think a lot of people struggle with this. What I did was I literally started to make “little bets.” So Little Bets, the book, really is an expression of what I learned through the years in my 30s when I was trying to figure out what to do with my life.

There’s a chapter at the end called “Dark Valleys.” There are many, many dark valleys and many, many setbacks. You know, I’d go into meetings and I’d be shaking; I wanted to just get a job. I can’t believe it, to think about it now, this was just a few years ago. I literally didn’t think I could get a job. I thought I was unemployable because I had confused everyone by being a venture capital investor, where I had an offer to go back to Summit and go on the partner track, and then I did this book project.

And then I went through this period where I had this conflict with Bill George, and people were like, “What the hell is wrong with this guy?” The only thing I can say is that I knew intellectually what I was actually trying to do. I had an amazing support structure around me, my family and my close friends, but it was really hard.

Just thinking about it, I almost cry. It was just so hard.

Q. What helped you project your own voice to get to where you are now?

A. It’s a great question. I really relied on people like Richard Tait being very open with me in the interview for True North. Richard had really gone through this transition from being a Microsoft employee to being a really creative entrepreneur.

You can just imagine those two extremes. It’s like, wow. How did you go from being a business development guy at Microsoft to a person who created Cranium, the board game company?

And he just talked about that. And I read that transcript dozens of times. And he’s a good friend of mine to this day. I love him.

Both my parents were very supportive. My dad is a judge. My dad had taken a very linear career path. Like people who are the kids of doctors or teachers or someone who’s been in the army — they’ve just taken very linear career paths, and all of a sudden, you’re saying to your parents, “Hey, I want to do something different. I want to try to find my bliss, follow my bliss.”

Both my parents had encouraged me to do that. They’d always encouraged that. But my dad especially had a really hard time understanding what the hell I was doing. And I didn’t even know what I was doing. And so, to have that conversation — I remember sitting with him at lunch — he just sat me down and said, “I’m really worried about you. Do you know what you’re doing?”

And I said, “Yes, I know what I’m doing.”

And I really didn’t. I mean, I felt like I just had to trust my intuition. So that’s really what I ended up learning, just to trust my own intuition. It sounds so simple, but the very specific examples are: if I met somebody I really liked, and I thought that they were somebody who I would want to potentially work with someday or collaborate with someday, or just have as a friend, I would keep in touch with them.

If it was a jerk, or just a complete a-hole, I would say, “You know what? Not only do I not want to be working with this person, or anyone near this person, but I don’t even want to have anything to do with him, because they’re just going to bring me down.”

I would stay away from those types of people, and there are some people like that. They’re not bad people. It’s just that they would give me advice; they would say “Peter, you should go back and work in investing. Go do what you’ve done. Stick to the knittings.” It’s like the old marketing advice, “Just go stick to your knittings.” And here I was, trying to do something very entrepreneurial and creative in terms of thinking about writing a book.

The only thing I can say, through those dark moments, where I was definitely depressed, not deeply depressed, but I was depressed, and my doctor would just say, “Hey, you have to hang out with people more. You have to exercise more.” And I would say, “All right. I’m on it.”

And I would be disciplined by just putting one foot after the other. And so, that’s where this whole notion of “little bets” was really meaningful personally to me — to just keep doing something.

You know, one of the biggest mistakes I made was that I would just get in my own head too much. And I just needed to get out into the world and do things, just do shit. Do shit that matters to you.

So, like, if you meet someone, and they’re doing something interesting, tell them you’ll help edit something for them. Start small. Then as you get into it a little bit, see if it interests you more, meet their friends, and just pursue it.

So what ended up happening was, I wrote the book, and I interviewed hundreds of people for this book. I spent two-and-a-half years. I had a whole research team at Stanford by the end, and I really became very close to George Kembel at the d.school. I started working on little side projects here and there, on education and education reform, things that were near and dear to me.

And so what happened after that was the BLKSHP evolved. See, my dream job would be to work at Pixar. I love Pixar. I go out there and it’s the most inspiring place in the world. You go there and there are literally these two giant cartoon characters from Monsters, Inc., staring you in the eye when you walk in the door. How can you not love that atmosphere?

I got to know a bunch of people at Pixar over time, very slowly. And I’ll give you a very specific example, just to show what the process is like, and how hard it is, and how many setbacks you have to overcome.

I was working on research for the book and I really wanted to try to connect with Ed Catmull, who is the co-founder of Pixar with Steve Jobs and John Lasseter. I had had a really, really hard time getting anybody to return my calls or e-mails at Pixar, even though I had already co-authored True North.

It just goes to show it’s really hard to get in some doors.

So I ended up going to a lecture that Ed Catmull gave at Stanford. I heard he was going to be there through some friend of a friend. You know, just keep your ear low to the ground, try to hear about stuff that’s going to interest you.

He’s there, and he gives this lecture, it’s a beautiful lecture, about Pixar’s culture and specifically the mistakes they’ve made and he’s made in particular. He was sketching outlines for what would become a book.

I went up to him afterwards, and I said, “Ed, I really appreciated your lecture. I’m Peter Sims.” He’s a very open guy. He’s just a great person. Anybody even just coming out of college can go up and talk to him — there were people up there talking to him who were recent Stanford grads or who were in school still. And he was answering them all the same. He was just a very down-to-earth, grounded guy.

I said, “Do you mind if I send you some feedback on your ideas?” And he said, “Sure.” He took out a card. He said, “I’d really appreciate that,” and he gave me his assistant’s card.

So I said, “Thank you so much for the lecture. I’m really looking forward to sharing some thoughts. I’ve thought a lot about this.” And so I went, and I spent two days, two work days, writing a memo to Ed Catmull. It was seven, maybe eight pages long. This was a long memo. I mean God help him, right? And I sent it to his assistant, and I didn’t hear back.

Now, you have to remember, I’m working on a book on creativity and innovation. I’m plugged into the design school. It’s not like I don’t have any credibility. It’s not like I don’t have some assets to work with. And that’s another way of thinking — just think about what you have that can be valuable to the outside world.

But he didn’t get back to me. So I ended up calling. You’ve got to be persistent. You’ve got to just call people and check in with them. I called his assistant, and I said, “Hey, did Ed receive my letter?” Because I spent a lot of time on this thing, but I didn’t say that to her. And she said, “He received the letter.”

Okay. Great.

Then months went by. I had gotten farther along in the book. And then there was some exhibit going on, where Pixar’s work was being displayed, and I went to go see this exhibit. It was in Oakland. I saw the exhibit and came back and I was so inspired that I wrote a short e-mail to Ed’s assistant to say how much I appreciated the exhibit.

He actually wrote me back that day, thanking me for the note, a really nice short note, and saying that he was thinking about potentially writing a book, and that he thought maybe he and I should talk about that sometime by phone.

And I said, “Great! Holy cow! What a great thing!” He was really needing advice, because he knew what I had to offer him. He knew what assets I could bring to the table.

Again, I put this in these terms. I don’t really like to use these terms, but the reason I do is because we think so much about the achievements, we think so much about the next award, the next accolade, that when you can just step away from that and think about: What do you know? What do you have? What have you learned? We all have so much to us.

But we just live in a world, unfortunately, that prizes the rational, the external, what’s ultimately the ego. So after Little Bets, I just wanted to work at Pixar, but I couldn’t draw. But I got to know Ed Catmull a little bit. Eventually, I introduced him to my literary agent, Christy Fletcher, who ended up representing him and it was a cool bond that started to shape. And, on my own, I had read everything about Pixar, read everything about Ed Catmull, read everything.

So I decided I didn’t want to work in my home office anymore. I wanted to work with my friends on cool, interesting problems, and do something like Pixar, or like the d.school. And since I couldn’t work at Pixar since I couldn’t draw, and the d.school has a culture that’s just quirky, some friends and I said, you know, we should create a space, a work space.

So that’s how we decided to create a work space, and I came up with the term “BLKSHP” because I had read an interview of Brad Bird from Pixar, who’s a director there. He’s one of the people at Pixar who was really willing to think differently about the status quo and use radically different approaches — artistic approaches — to solve problems in new and different ways, and he had used this term “black sheep” to describe people with unconventional ideas.

And that was just so inspiring, so we said we’ll call it “BLKSHP.” And then with my friend, Andy Smith, who’s another author here in the Bay Area, who is married to Jennifer Aaker, who’s a Stanford professor — this little group of people started to become my group of peers and professional support in all this. Out of that grew this chance to collaborate to create a work space, which we call BLKSHP.

And this is all just a manifestation of “little bets.”

So the company today does three things. We create for-profit businesses that can generate income to fund social entrepreneurial ventures. An example would be one of our businesses called “Think Differently” by BLKSHP. That name may change, but what we do is innovation advisory services.

Corporate innovation audiences or creative audiences will say, “Well, how do we make little bets?” For example, I’m on the innovation advisory board at General Electric now. So it’s a way of taking those opportunities that are coming in by virtue of this asset that’s been created with the book to then monetize it.

So that’s really I think the key intellectual switch that flipped, is to think about, “How can you take your assets, create value for the world, and then monetize that?”

Think about it in terms of a balance sheet, instead of an income statement. If you think about your career in terms of a balance sheet instead of an income statement, then you’re not worried about trying to grow each step of your career to some little step higher, to a little step higher, to a little step higher. It’s all artificial anyway. You’re thinking about how you can take your experiences and create value for the people you’re working with, for society.

So you have all these assets; everybody has assets and you can constantly build assets. And once you have one asset, it can lead to another asset. So a book, obviously, is a great asset, because then it can lead to a creating a company like an innovation advisory firm.

So that’s what we’re doing. I’m collaborating right now, likely partnering with Casey Haskins, whom I interviewed for the book. Casey is the former head of military instruction at West Point. He trained all the cadets on how to prepare for asymmetric warfare. This is what all these companies are trying to solve — it’s how do we think in a more creative and adaptive way, starting at the strategic layer.

So lots of innovation type of work. But we have a lot of fun. We learn a lot, and I really like working with Casey. I can be me, and he can be him, and we can have a Pixar-like culture for BLKSHP, even though it’s like a networked organization.

And then, with that, we’re going to use the proceeds and profits of that to fund things like allowing people like yourself to develop their own voices, to give people a creative place. So we have people come to BLKSHP who would be entrepreneurs-in-residence or artists-in-residence, basically give them a business card, a calling card, and then we partner with groups like Forbes and the 92nd Street Y in New York. We’re going to do a lecture series in partnership with them next year on topical issues around social entrepreneurship. We really do a lot of different things.

So, Pixar is the dream culture and values. Another company I also really admire and is certainly a model in many real ways is Virgin, because you can hang a lot of different businesses under a brand that is aspirational and that connects with a sense of humanity — and still make a great business.

BLKSHP is a B Corporation. It’s a socially beneficial corporation. I’m not in this to make billions of dollars, but I would like to have this group of people I’ve been fortunate enough to get involved with, including Domingo Rodelo, who is our creative lead and who I’ve known for three or four years.

I met him at a friend’s birthday party and he was writing copy for a marketing firm before coming on to BLKSHP. He is now doing everything. He’s a filmmaker. He’s a photographer. He’s managing a creative team of extremely talented creative people, both people who are on the payroll or who are partnering with us on different things like the 92Y or what-have-you.

Then we have another guy who I met on the beach. I literally met Russell Robinson on the beach in Barcelona this summer. And I was just blown away by his humor, insight, and creativity. He is now our brand guru. He’s our chief artistic person. He helps Casey and me, and we’re doing a music business as well to really develop our voice, our brand, our approach to the outside world.

We’re also looking at doing things in publishing, that was one of the original intents of getting this group together, and it’s just taken on a life of its own. All I’m trying to do is help it off the ground and then step back into a role that’s less intense because I’m really, as you know, exhausted from this all.

Q. In your book Little Bets, you talk about the research Richard Wiseman, the psychology professor, has done on luck. In particular, you talk about how he’s found that one common trait of “lucky people” is that they build and maintain a strong network.

I quote: “Lucky people are effective at building secure, long lasting attachments with people they meet. They are easy to know and most people like them. They tend to be trusting and form close relationships with others. As a result, they often keep in touch with a much larger number of friends and colleagues than unlucky people. Time and again, this network of friends helps promote opportunity in their lives. Extraversion, Wiseman found, pays opportunity and insight rewards.”

Given that some people are better at building a network than others, and a lot of folks are introverted by nature, what advice do you have to get better at building genuine relationships?

A. That’s a great question. I’ve never been asked this in an interview.

I’ll give you an example. I was in New York last Monday at this event. I paid $200 to support Scott Harrison and charity: water. Actually, I paid $400 because I paid for myself and a guest. I went with a woman who’s a wonderful person, just a friend, Valentina Kova.

She spots across the way Whoopi Goldberg. Whoopi Goldberg was at this event. It was a huge event. There were tons of people there. She says, “I would love to meet Whoopi Goldberg. Do you want to go meet Whoopi Goldberg?”

I was like, I mean, “I guess.” I remember Whoopi Goldberg from The Color Purple and Sister Act. I don’t watch The View, but I’ve learned that she’s on The View.

Anyway, we go over there. We’re standing there. And a couple of things — one is, when I was at Summit Partners, we had to cold-call entrepreneurs. This was very hard for me, being an analytical guy, to cold-call people. And so, I learned through lots of failure and setbacks that you just do it. You just keep doing it and these are little bets. It really is little bets, actually, looking back at cold-calling.

I’ve done so many little bets meeting people. I told you earlier, I learn by talking with people. I’m not a very good classroom learner, but I’m a very curious person. And it’s very rare that I meet someone that I just don’t enjoy meeting.

In the case of Whoopi Goldberg, Valentina introduced herself. She said a few words, and then she said, “Do you know Peter Sims?” And she turned to me, and I’m like, “Yeah. How is she going to know Peter Sims?” So she said, “Peter is a best-selling author,” which is half true. I mean, I was co-author of a best-selling book, and Little Bets has won a lot of awards, but it wasn’t like a New York Times bestseller.

And then she said, “Oh, you know, he’s the author of this book, Little Bets.” And Whoopi Goldberg looked at me and she said, “I’ve heard of Little Bets. You wrote Little Bets?” I said “Wow.” I was shocked. I said, “Yes, I wrote Little Bets.” And so I was a bit overwhelmed by that. But then I asked her where she’s from.

She’s describing where she’s from, and I get a little bit about her passion. I always ask people where they’re from to start, rather than talking about their title because — I learned this from True North — everybody’s values are really shaped from their earliest days.

Now, here’s what happened with Whoopi Goldberg. Valentina was nervous. Valentina is so humble that she was nervous. And this happens a lot, right? People don’t think that they’re worthy of talking with someone. But I always look at everyone — whether it’s you, or a guy who has gone to my high school, or Whoopi Goldberg, or the President of the United States — I look at them as a human being. They all have their stories. We’re all shaped by our stories in life.

This is what True North is all about — authentic leadership, its all about stories. You had a scout master who had a big impact on you, or Howard Schultz grew up in the projects in Brooklyn. I mean, that’s how we connect, is through our stories.

So then, Valentina was saying how I had co-founded Fuse Corps. Fuse Corps is this really cool program where you go spend a year working with a mayor, governor, or social entrepreneur. You get paid a nice stipend. It’s a very highly selective program. This is like the Rhodes Scholarship for social change.

I told her the example of how Erika Dimmler was a CNN producer, and then she left her CNN producership to go work for Mayor Kevin Johnson in Sacramento as his chief of staff. The goal was to solve this problem, which is “How do you bring healthy eating into the Sacramento unified school district?”

So instead of starting with the answer and telling people how to change the school system from Washington, Erika Dimmler went in and talked with the teachers and students, the citizens, the people who have the needs and the problems.

And I went to see Erika’s launch of this thing. And the kids are holding shovels and hoes. It’s like “Wow.” This is design. This is Little Bets. This is entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, at it’s best. And they’re planting a whole friggin’ garden in the school district, right in the middle of the school district.

And this is so inspiring to see, and I’m telling Whoopi Goldberg this story, and she said, “That’s cool. That’s cool you were involved with that.” I mean, I co-founded this, I’m very active, I spend 20-25 hours a week on Fuse Corps, in addition to speaking and doing BLKSHP business.

She’s like, “This is so cool. This is so inspiring. You know, what you do need to do, though, instead of working on a high-end project,” because Alice Waters, the chef of Chez Panisse is involved with this Sacramento project, “since they’re working with Alice Waters, you guys should be working to help very, very poor people to plant gardens.”

This is such a cool idea that I said to her, “Listen, Whoopi, where I grew up, in the foothills of Northern California between Sacramento and Tahoe, my neighbors in the town of Dutch Flat — this tiny gold mining town — they’re doing the same thing.” So she and I were able to connect through our stories on that level, and I said to her, “We should do a Fuse Corps fellow to tackle this problem.”

She’s like, “You know what, I would love to do that, Peter.” It was like, it had made her day to connect with someone in that way, in a very human way, and to be able to do something she cared about and feel like she wasn’t alone and to be able to say, “Okay, here’s my e-mail address.” And she gave me her e-mail address.

I wrote her an e-mail, just saying how it was nice to meet her, how excited I was to lock arms with her in a really collaborative spirit, like, “Let’s find out how we can raise this money and let’s go find a project, and let’s just pull in whoever we need to pull in to do this.” I mean it’s Whoopi Goldberg — we should be able to do it pretty easily, right?

So she writes back, and she’s excited and she signed it “Whoop.”

So, anyway, that’s an example of the type of stuff that happens after years of just being curious.

My parents are very genuine. I think I’m a genuine person. My intentions are pretty open. I’m very transparent with people. I don’t try to be someone I’m not anymore. I used to when I was in the more “external phase.”

That’s one of the things that rubbed Bill George the wrong way, is that I wasn’t comfortable being the authentic leader example. I wanted to be the co-author. But it was Bill’s book and he gave me the opportunity. So it’s understandable that he would feel some frustration that I was challenging him on that. But the fact of the matter is, here we are, I’m 36, and I never would have guessed when I was growing up that I would be doing what I’m doing.

I’m an entrepreneur who’s very improvisational, with the people who work with me now. I’m an entrepreneur within a set of constraints that are my values and ethics and a framework that is informed by working in venture capital and having the good fortune of going to Stanford and getting an MBA and learning from a lot of people.

So that, to me, is a great gift. And I do feel like, with conversations like these, I’ll take a little bit more time even though I’m tired and I’m supposed to be really just relaxing right now after a crazy week. But I hope there may be something here for you or for the people watching this. When I was going through many difficult experiences, many, many, many setbacks, many moments of loneliness, many moments of hardship and depression, moments where I even felt suicidal, I just kept putting one foot in front of the other. Keep making little bets. Keep learning. Keep listening. Keep open, and just follow your heart.

That’s what Howard Schultz signed in my book right after we interviewed him. He signed my book. He was gracious to sign my book and say that he felt like I was going to be very successful and he wanted to follow my progress. But he also said, “Just follow your heart and believe in your dreams.”

And I’ve tried to impart that wisdom to others, because that’s really what I ended up doing. It’s all clear in hindsight. I love this expression — Randy Komisar taught me this. He said, “Everything’s clear in the rear-view mirror, but you can’t see where you’re going when you’re looking through the front window.”

So you just have to keep at it and keep finding people you really love. Believe in yourself. Be you. It’s that simple.

You just have to keep pushing. Keep being you. Everybody has a role in life. You have your role; I have my role. If I can help you to do your role in life better and we can collaborate on stuff, we’re going to do a lot of cool things over time. That’s how things really happen; it’s collaboration.

You just have to be you and realize that, at the end of the day, you’re going to have to take that feedback people give you and just do the best you can everyday. And I think that’s all everyone wants to do. Just do the best they can everyday and lead a life where they can be themselves. It’s really that simple.

And that only happens with collaboration, because if there’s too much ego involved, where it’s all about one person, you just can’t really get as much done.

You know, Ronald Reagan said it best. I’m paraphrasing, but he said something like, “You can get a hell of a lot done if you don’t care who gets credit for it.”

Q. You wrote how one aspect of the “little bets” approach to innovation is that it focuses you on what you can afford to lose rather than how much you can expect to gain.

If you apply this to the way young people approach their careers, what are little bets people can make as they search for their own career calling?

A. That’s a great question. I’m really glad to end on this one because we so often think that we have to be perfect to do something new. You have to get something perfect; it has to be just right.

And that’s not the way creativity works. When Howard Schultz founded Starbucks — I like to tell this story a lot, because Howard is a visionary in many ways. He has incredible foresight, incredible marketing and branding insight, and a hell of a leader, a hell of a motivator. But when he went to Italy and was inspired to start Starbucks, he came back and he started a store that became Starbucks.

He eventually bought what was then Starbucks. Starbucks was a small chain of coffee stores. But he started this thing called Il Giornale, which was one coffee store, modeled on the Italian coffee experience, that had non-stop music playing. They had the menus in Italian. The baristas were wearing bowties, which they found very uncomfortable, and there were no chairs.

There were no chairs in the first Starbucks! Can you believe that? No chairs. It’s very different today. So Howard says they had to make a lot of mistakes to discover what was going to work.

And so a “little bet” and an affordable loss is saying upfront that you don’t know if it’s going to work or not. And just keep thinking about what you can do that’s simple, that you’re interested in. You just have to try it.

It’s like with comedians. If you see Chris Rock — this is an example I use a lot — they’re perfect on the big stage, but when they’re starting out in small clubs, developing material, which is where all comedians have to develop material, they suck. They suck. Don’t let anybody tell you otherwise, because that’s how creativity works. Chris Rock doesn’t even let people use their cellphone cameras when he’s up there.

This is the reality of what it takes. But six months later, he’s ready with a one-hour act. He’s tried every joke, every transition, everything else.

So anyway, thank you for doing what you’re doing, Andrew. You’re doing a great service, and I hope that your listeners and readers take some insight from this. I never get asked these questions. It’s a little bit odd to have talked about myself for as long as we have, especially when I thought we were going to go in less time, but the reason I did is because the only way I was able to get through my very, very difficult transition was by this process of discovery and little bets, and by having people around who were willing to be open with me about their experiences, especially their setbacks and failures.

And Bill George is one of the most open people I know, and he’s absolutely one of the people who deserves a great deal of credit for that, and a lot of the other interviews we did as well. All these people played a really formative role in the end, even though getting there was quite difficult.

Leave a Reply