An easy summary of the Trump tax bill

| Key benefits of Trump tax bill | Key drawbacks of Trump tax bill |

|---|---|

| Lower income tax rates | Personal exemption eliminated |

| Bigger standard deduction | Capital gains tax rates no longer linked to income tax rates (more complicated) |

| Bigger child tax credit + higher phaseout threshold | Mortgage interest deduction only good for <=$750k mortgage debt, down from $1M (hurts coastal states) |

| Pease phaseout eliminated for itemized deductions (benefits high earners) | SALT deductions capped at $10k (incl. property taxes, hurts coastal states) |

| AMT: higher exemptions + much higher phaseout (so AMT now much less relevant) | Roth IRA recharacterizations eliminated |

| New 199A deduction up to 20% qualified business income | 1031 exchange value less certain due to 199A considerations |

| Estate tax exemption doubled (so estate tax now much less relevant) | 199A deduction gets complicated fast, doesn’t help white collar pros, high earners, or capital/labor efficient biz (e.g., software, contracting biz) |

| 529 plans can now be used for K-12 | Eliminates many deductions like all misc, biz entertainment, moving expenses, etc |

Unless you were under a rock last year, you may remember that just before 2018, Trump’s Congress passed a sweeping new tax bill, the most significant tax code overhaul in decades.

The key changes most relevant to wealth hackers and early retirees are summarized in the table above. In this post, I provide a “dummies” explanation to help folks understand:

- What the Trump tax bill means to me?

- Will the Trump tax bill affect me?

- Will the Trump tax bill help me or hurt me?

The post has 5 sections:

- W-2 income

- investment income

- real estate income

- side hustle/business income

- estate planning and 529 plans

First, some high level questions.

Background on Trump tax bill

Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (full text of bill) was passed by Congress on December 20, 2017, signed into law by Trump on December 22, and most changes kicked in January 1, 2018. The bill’s provisions are not retroactive and 2018 is the first full year the bill applies, which means it’s relevant for the tax filing season that is starting now.

While the corporate tax code changes are permanent, the individual tax code changes will automatically expire after 2025 and revert to Obama-era rules, unless renewed by Congress. The reason is because of a rule (Byrd Rule) that only allows legislation to pass the Senate with a simple majority if it does not result in net tax cuts beyond 10 years (else, you need 60 votes to block a filibuster).

While it’s not guaranteed the individual tax code changes will survive past 2025, Republicans are hopeful they can make the changes permanent because between 2025 and 2026 there will be a big tax/fiscal cliff that will motivate legislators to do something. That’s how/why the Bush tax cuts, which were also designed to similarly expire, were ultimately made permanent.

Who are the winners who will benefit most from Trump’s tax bill?

Before diving into nitty gritty details, here’s a mental shortcut for “who benefits most from the Trump tax bill”:

- Families with one or fewer kids

- People who live in the middle of the country (non-coastal states)

- People owning small businesses and working for themselves who make between $0 – approx. $400k, or who make $1M+ (i.e. small business owners who are either middle/upper-middle class or super rich)

- People whose owned businesses have a lot of depreciable assets or labor costs

- Rich people who have a lot of assets to bequeath to heirs

In particular, if you have few dependents and are income-poor but asset-rich (e.g., early retirees), the new bigger standard deduction creates opportunity for bigger Roth IRA conversions.

Who are the losers who benefit least from Trump’s tax bill?

- Families with more than one kid

- People who live in expensive coastal states

- People who own a home w/ high property taxes

- People who work W-2 jobs who make between approx $400k – $1M

- People who live in high-tax states (SALT deduction capped)

- People who regularly entertain business clients for their business (e.g. sales)

- White-collar professionals whose partnerships, LLCs, consulting companies, etc, make more than approx $415k married, $207k single

- People who used to itemize a moderate amount of deductions, especially misc deductions

What does the Trump tax bill mean for families?

- Bigger child tax credit

- Greater flexibility for 529 plans

- Much less likely to be subject to AMT

Breakdown of how the Trump tax bill works: W-2 income

Tax brackets

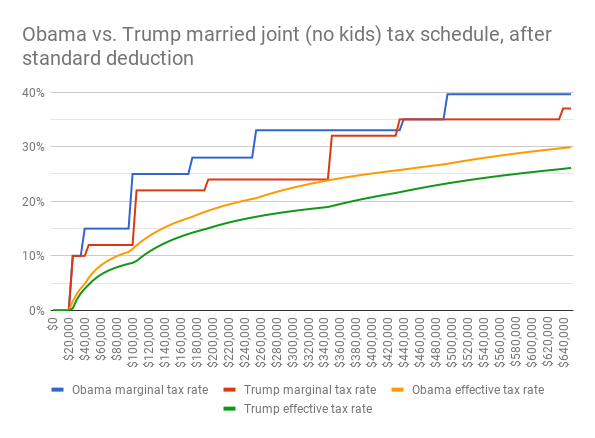

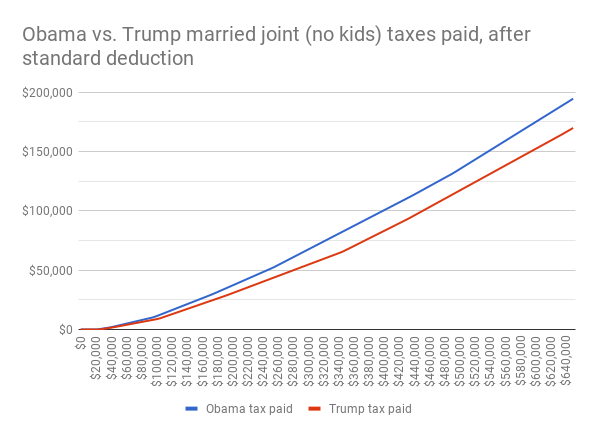

The Trump tax bill reshaped ordinary income tax brackets and tax rates, but not as drastically as Congress originally planned. Rates are generally a little bit lower, however.

These are the changes for married joint filers:

Under Obama| If you make... | ...your 2017 marginal rate is... |

|---|---|

| $0 - 18,650 | 10% |

| 18,650 - 75,900 | 15% |

| 75,900 - 153,100 | 25% |

| 153,100 - 233,350 | 28% |

| 233,350 - 416,700 | 33% |

| 416,700 - 470,700 | 35% |

| $470,700+ | 39.6% |

| If you make... | ...your marginal rate is... |

|---|---|

| $0-19,400 | 10% |

| 19,400-78,950 | 12% |

| 78,950-168,400 | 22% |

| 168,400-321,450 | 24% |

| 321,450-408,200 | 32% |

| 408,200-612,350 | 35% |

| $612,350+ | 37% |

A more visual depiction:

Standard deduction + personal exemption

As well, the standard deduction doubles under Trump’s tax bill, while the personal exemption got eliminated:

Standard Deduction + Personal Exemption| Filing Status | 2017 Obama | 2018 Trump | 2019 Trump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | $6,350 | $12,000 | $12,200 |

| Married Jointly + Surviving Spouses | $12,700 | $24,000 | $24,400 |

| Married Separately | $6,350 | $12,000 | $12,200 |

| Head of Household | $9,350 | $18,000 | $18,350 |

| Personal Exemption | $4,050 | $0 | $0 |

| Additional standard deduction for 65 and older or blind taxpayers | $0 | $1,300 / married payer $1,600 / unmarried payer | $1,300 / married payer $1,650 / unmarried payer |

Because of this, fewer people will itemize deductions (simpler tax returns), but this is worse for families with more children, better for childless taxpayers.

For example, for married joint filers, here’s how much tax-free income you get before rates kick in:

How much tax-free income married joint filers get before rates kick in| Number of kids | 2017 Obama | 2018 Trump | 2019 Trump |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $20,800 | $24,000 | $24,000 |

| 1 | $24,850 | $24,000 | $24,000 |

| 2 | $28,900 | $24,000 | $24,000 |

| 3 | $32,950 | $24,000 | $24,000 |

Child tax credit

To not totally screw large families, the Child Tax Credit increased from $1,000 to $2,000 per child (at least through 2025). But there are new rules, too:

1. Part of the credit is refundable. For both 2018 and 2019, up to $1,400 (indexed for inflation) of the $2,000 is refundable if you don’t wind up owing any taxes. By contrast, in 2017 and earlier, unused/leftover credit was forfeited. Instead, there was an Additional Child Tax Credit (now eliminated under Trump’s tax bill) that was potentially refundable.

To get the new refund, you must have earned income (job or self-employment). You get refunded 15% of earned income over $2,500. So, you need to earn ~$12k to get the full $1,400: $12k – $2.5k = $9.5k. 15% x $9.5k = $1,425, and refund capped at $1,400. Compare to the old Additional Child Tax Credit where you’d need to earn more than $3k to get any additional credit.

2. Phaseouts are much higher now. The credit starts phasing out once you earn too much, but the threshold where that phase out begins (based on MAGI) was increased a lot. The old thresholds: $110k married joint, $55k married separate, $75k everyone else. New thresholds: $400k married joint, $200k everyone else. Each $1,000 earned over the threshold reduces the credit by $50.

Pease phaseout

Previously high earners who itemized deductions would have those deductions phased out once their income exceeded a threshold. This was called the Pease phaseout. It applied to charitable deductions, home mortgage interest, state and local tax deductions, and other misc itemized deductions, but not medical expenses, investment expenses, gambling losses, or certain theft and casualty losses.

Under Trump’s tax bill, the Pease phaseout is eliminated (through 2025), so you can now take these deductions no matter your income level.

Alternative Minimum Tax

Despite initial talk of repealing AMT entirely, it survived the final version of Trump’s tax bill. However, the exemption amount was increased significantly:

AMT Exemptions| Filing Status | 2017 Obama | 2018 Trump | 2019 Trump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | $54,300 | $70,300 | $71,700 |

| Married Jointly | $84,500 | $109,400 | $111,700 |

| Married Separately | $42,250 | $54,700 | $55,850 |

| Trusts & Estates | $24,100 | $24,600 | $25,000 |

The exemption phase out for high earners also increased dramatically. It starts phasing out at a rate of 25 cents per dollar earned after AMTI exceeds a certain threshold:

AMT Exemption Phaseout| Filing Status | 2017 Obama | 2018 Trump | 2019 Trump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | $120,700 | $500,000 | $510,300 |

| Married Jointly | $160,900 | $1,000,000 | $1,020,600 |

| Married Separately | $80,450 | $500,000 | $510,300 |

| Trusts & Estates | $80,450 | $82,050 | $83,500 |

Whereas before, AMT started kicking in at ~$150k+ income, now the vast majority of taxpayers won’t be impacted by AMT at all. Higher AMT phase out thresholds and fewer deductions (more on this later) both contribute to this. So unless you are a top 1% earner or have a very large AMT adjustment/add-back (like exercising extremely in-the-money stock options), no more AMT for you.

Another happy benefit: If you paid lots of AMT in the past, you generated significant Minimum Tax Credits. But usually you couldn’t actually use them because you were paying AMT every year. Well now, you can use them. With the increased AMT exemptions/phaseouts, you’ll now have a bigger gap between your normal vs. AMT tax liability, so you can start “filling up that gap” by claiming back your carryforward AMT credits.

Breakdown of how the Trump tax bill works: investment income

Capital gains tax rates

The biggest change here is for long-term capital gains tax rates. Previously long-term rates were based on your income tax bracket:

| If your marginal tax bracket was... | ...your LT capital gains tax rate was: |

|---|---|

| 10% | 0% |

| 15% | 0% |

| 25% | 15% |

| 28% | 15% |

| 33% | 15% |

| 35% | 15% |

| 39.6% | 20% |

But now, under Trump’s tax bill, the rates are based on specific dollar amounts of taxable income, not tax brackets.

For 2018 tax year:

| Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Rate | Single (taxable income) | Married Joint | Head of Household | Married Separate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | $0-38,600 | $0-77,200 | $0-51,700 | $0-38,600 |

| 15% | $38,601-425,800 | $77,201-479,000 | $51,701-452,400 | $38,601-239,500 |

| 20% | $425,800+ | $479,000+ | $452,400+ | $239,500+ |

And for 2019 tax year:

| Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Rate | Single (taxable income) | Married Joint | Head of Household | Married Separate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | $0-39,375 | $0-78,750 | $0-52,750 | $0-39,375 |

| 15% | $39,376-434,550 | $78,751-488,850 | $52,751-461,700 | $39,376-244,425 |

| 20% | $434,550+ | $488,850+ | $461,700+ | $244,425+ |

Roth IRA recharacterizations

Previously you could recharacterize Roth conversions (i.e. backdoor Roth) after the fact. You could convert from traditional to Roth, and then undo the transaction later.

The reason why you might do this is because, back in the day (original 1997 Roth rules), there were income limits that determined whether you could contribute or convert to Roth. Some taxpayers who thought they would earn less than the income limit later found out after the year was over they actually earned more than the limit (e.g., a high bonus). So then they’d have to recharacterize/undo any Roth contributions/conversions. The purpose was to help people who went over the limit not get penalized.

But then the income limits for Roth conversions were repealed in 2010 (Pension Protection Act). So the original purpose/benefit for an undo became obsolete. Meanwhile, recharacterizations were still being used in two extremely useful but unintended ways: (1) for early retirees, not having to calculate/guess exactly how much to convert to Roth to fully “use up” their standard deduction / personal exemptions each year because you could simply recharacterize any excess by April 15 the following year; and (2) strategically hyper-optimizing conversions (advanced technique): specifically, you could make multiple conversions to multiple separate empty Roth accounts at the beginning of the year, see which ones performed best by April 15 the following year (i.e. up to 15 months later, or even up to 21 months later if you filed for October 15 extension), keep the winners and recharacterize/undo the losers.

Under Trump’s tax bill, you can still do Roth conversions, but recharacterizations are no longer allowed, so these optimizations don’t work anymore. Now, you must actually carefully estimate how much conversion will “fully use up” your standard deduction and convert that before December 31 to get credit for it, and you cannot recharacterize any excess. Likewise, you cannot “over-convert” and wait to see which lots are winners vs. losers and recharacterize the losers anymore.

Breakdown of how the Trump tax bill works: real estate income

Some big ones here.

1. State and local tax deductions capped at $10k. aka SALT deductions. Previously you could deduct all your state and local taxes including property taxes. Under Trump’s tax bill, SALT deductions are now capped at $10k annually. This is the same for both single and married filers (marriage penalty), $5k cap if married filing separately. This hurts coastal taxpayers in mostly blue states where state and local property taxes commonly exceed $10k per year. It rarely impacts middle country taxpayers in red states because home values (property taxes) there tend to be much lower.

2. Mortgage interest deduction capped at $750k initial acquisition debt. Now you can only deduct mortgage interest on the first $750k of mortgage (vs. $1M under old rules). The mortgage must be used to acquire, build, or significantly improve a primary residence or designated second home. Note that when you refi old (pre-2018) acquisition mortgages you can keep your $1M limit but only for remaining debt, not additional new debt.

For non-acquisition home equity debt, the interest deduction is eliminated, and it’s retroactive, so you can no longer deduct any interest on existing home equity loans or HELOCs whose proceeds were used for “non-acquisition” purposes.

They key here is: what was the mortgage debt used for? Acquisition debt is used to “acquire, build, or substantially improve.” It has to be for your primary or designated second home. Non-acquisition debt is debt used for anything else (vacation, credit cards, college tuition, car, etc). In either case it doesn’t matter whether the debt was via home equity loan, HELOC, or traditional 30 year fixed. A HELOC for a house expansion still counts as acquisition debt. A 30-year fixed cash-out refi to pay for junior’s college tuition does not.

3. 1031 exchange value is murkier now because of Sec. 199A. Two things. One: previously 1031 exchanges were allowed not only for real estate but also other types of investment property like boats or vintage cars. Under Trump’s tax bill, it now only applies to real estate (equal or greater value).

Two: the new Sec. 199A deduction makes the value of a 1031 exchange not as clear-cut anymore. Some real estate investors are better off foregoing a 1031 because 1031 and 199A sometimes conflict with each other. Specifically…

- the more your old property has appreciated…

- the more depreciation you’ve already taken (i.e. you sell decades later, not years)…

- the more your old property value is allocated to building and not land…

- the higher your marginal tax bracket…

- the more you believe Congress will extend Sec. 199A past 2025…

…the better off you are NOT doing a 1031. Instead, pay capital gains taxes on a sale now and then buy your new property outright. Here’s why.

Sec. 199A gives real estate investors a potential deduction of 20% of income earned on a property. Income here = net operating income (NOI) less depreciation, as reported on Schedule E. However, if you Mr. real estate investor are a high earner (taxable income >$207.5k single, >$415k married), then extra rules apply. Your 199A deduction cannot exceed the greater of two amounts:

- 50% of wages paid by your RE business

- 25% of wages paid + 2.5% of your original depreciable basis (i.e. before any depreciation taken) that is allocated to buildings (not land)

Most RE investors pay no wages because they’re one-man shops, so many high earners here are capped in terms of 199A to 2.5% of original basis.

For how many years can you take the 199A 2.5%-of-basis deduction? Answer: however many full calendar years you’re depreciating your property. The 2.5%-of-basis analysis is done based on your basis value on December 31 each year. So if it’s a new residential property, you’re probably looking at ~27 calendar years (residences are depreciated over 27.5 years). If it’s commercial property, then at least 38 calendar years (CP depreciated over 39 years, but you might have purchased mid-year).

However, when you do a 1031, several bad things happen to your 199A deduction:

- You don’t get 199A deduction on the new property for the full 27/38 years because your countdown clock doesn’t reset to zero, it continues where your old property left off and you only get to burn off remaining time (i.e. 27/38 years less however many years you owned your old property)

- Since your new property’s basis will be low (i.e. equal to your old property’s basis which has been depreciated), you don’t get the 2.5%-of-basis deduction against a high basis asset, you get it against a low basis asset (assuming you even have any basis left). If the gap between high vs. low here is big, then you’re missing out on deducting 2.5% of that gap. Every year. Potentially for decades. The size of that basis gap = depreciation already taken + market appreciation of the property.

This is all pretty abstract, huh. Here’s a little example to illustrate:

- Say you bought a residential property 10 years ago for $1M, $800 allocated to depreciable building, $200k to non-depreciable land

- You depreciate $300k over the next 10 years

- During the same period, the property’s market value appreciated to $2M

- 1031 scenario

- You do a 1031 into another $2M property, $1.6M allocated to depreciable building, $400k to land

- Your carry-over basis is $500k ($800k – $300k) not $1.6M

- So your basis gap is $1.1M ($300k depreciated + $800k appreciation)

- Your opportunity cost is up to 2.5% x $1.1M = $27.5k. For the next 17 years (27 calendar years – 10 already spent). That’s up to $467.5k spread over 17 years.

- No 1031 scenario

- You decide to sell but no 1031. You sell for $2M, $1.6M allocated to depreciable building, $400k to land

- You pay capital gains tax: 25% on depreciation recapture of $300k + 20% on appreciation of $1M (building appreciated $800k, land $200k) = $75k + $200k = $275k

- But now your new property depreciable basis $1.6M, which you can deduct up to 2.5% against. Every year. For 27 years, not 17!

Now you see how 1031 and 199A are in tension. By doing a 1031, you defer $275k of taxes now, but forfeit up to $467.5k over 17 years: you reduce both the size of your 199A deduction and its lifespan. By NOT doing a 1031, you pay $275k taxes now, but you get up to $1.08M in 199A deductions ($40k annually for 27 years): you get both larger and longer 199A deductions. I say “up to” in both cases because the actual deduction amount could be lower. 199A deduction = 20% of QBI (qualified business income), and for high earner RE investors, it’s further capped at 2.5% of depreciable basis (i.e. you take the lower of the two).

So you either pay capital gains now and get high basis in your new property in exchange vs. defer taxes for now (1031) but get low basis.

Also remember, any taxes saved/paid right now are present value. Whereas 199A deduction is annual. You need to factor in the time value of money here. You have to run the numbers to figure out which one (save/pay taxes now vs. take 199A over time) is better off.

You also have to be OK with the risk/uncertainty of a long time horizon (e.g., what if Congress does not extend 199A past 2025?). The bigger the 199A “reward” is, the more willing you’d be to forego 1031 tax savings and “roll the dice.”

So, earlier I said the more that 5 things are true, the better off you are NOT doing a 1031. Now you can see why:

- the more your old property has appreciated, the bigger the basis “gap” will be b/t old vs. new property hence the greater the 199A opportunity cost

- the more depreciation you’ve taken, same thing: the bigger the basis gap

- the more your old property value is allocated to building and not land, the more basis can be used to apply 199A (and therefore the higher your 199A cap)

- the higher your marginal tax bracket, the greater the opportunity cost of forfeiting 199A: since 1031 defers depreciation recapture (25% tax rate) and capital gains (15-20% tax rate), whereas 199A gives you a 20% income tax deduction off your marginal tax rate which could be 35% or 37%

- the more you believe Congress will extend 199A past 2025, the longer you will be able to claim the 199A deduction. Whereas if you believe Congress is not likely to extend, it probably never makes sense to forego a 1031. (As of right now the law says 199A expires after 2025 so you’re only guaranteed to enjoy/forfeit 7 more years of 199A deductions…for now)

Bottom line: I’m not saying a 1031 is now bad. I’m saying, if you’re a high earner RE investor, actually take the time to run the numbers. That’s the only way you’ll know for sure. If you’re not a high earner, don’t worry: you’ll get your 199A deduction because you won’t be limited by the 2.5% of basis rule anyway.

One more important thing. A RE investor’s business activity must rise to the level of a Sec. 162 “trade or business” to qualify for 199A deduction. There is some case law on this and IRS rulings you can look up, but basically your RE investing activity must have “regularity and continuity” as well as a “profit motive.” It cannot be “sporadic” or a “hobby.”

OK, I’ve covered the gist of things here, but there are actually some more nuanced details that may or may not be relevant to you. See Stephen Nelson’s excellent post if you want more gory details (including helpful examples).

Breakdown of how the Trump tax bill works: side hustle / small business income

1. Sec. 199A gives a potential 20% tax deduction to side hustles/businesses. Trump’s tax bill introduced a very important new tax deduction explained above: Sec. 199A. 199A allows pass-through entities – partnerships, LLCs, S corps, sole props filing Schedule C – to potentially get a lower tax rate on QBI (qualified business income). The deduction is “below the line” (after AGI is calculated) but not itemized, so you can still claim it even if you take the standard deduction.

But you should know some things:

One: The 199A deduction = 20% QBI or 20% of your taxable ordinary income, whichever is less. You only pay taxes on the other 80%. However, if you’re a high earner whose taxable income (not taxable ordinary income, and not AGI, but taxable income after deductions) is >$207.5k for singles, >$415k for marrieds, then your 199A deduction is limited to the greater of two amounts (…unless you’re an SSTB which I’ll explain in a minute): (i) 50% of total wages paid to all employees, or (ii) 25% of such wages + 2.5% of unadjusted depreciable property basis. Remember, taxable income = all income including passive/rental income, capital gains, Roth conversions, etc. See Stephen Nelson’s post on this for more details.

Two: Investment income doesn’t count as QBI. Nor do wages paid to the business owner.

Three: The rules do not allow employees to benefit much by reclassifying themselves as pass-through businesses / sole prop contractors for the purpose of treating their wages as QBI. Your friendly congresspeople foresaw that loophole.

Four: If you’re a high earner who busts the taxable income threshold (again, all income not just ordinary income), and you work in an SSTB (specified service trade or business), you don’t get 199A. At all. It simply doesn’t apply to you. SSTBs are basically white-collar professionals and celebrities: doctors, lawyers, all consultants / independent contractors (which is what employees who reclassify themselves are), accountants, actuaries, financial planners, entertainers, athletes…and any other job where the principal asset = your reputation/skill. Sorry, you’re SOL.

Five: Since 199A applies to pass-throughs, each partner in the business must calculate their own 199A deduction on their individual tax return, based on their own taxable income. Since equal partners may have very unequal taxable incomes, the amount of deduction allowed can vary between partners.

Six: Just as worker bees may think of reclassifying themselves, professional services firms like accounting/law firms, whose rich partners typically bust 199A thresholds, might consider converting into (or elect to be taxed as) corporations. Under Trump’s tax bill, the top corporate tax rate is now only 21% vs. the top individual tax rate of 37%.

Seven: Are you using some QBI to contribute to a retirement plan, like a 401k/IRA? This will reduce your 199A deduction. Either by reducing QBI directly (S corps), or by reducing taxable ordinary income (partnerships, sole props). Remember your 199A deduction is 20% of the lower of these two amounts. So putting QBI into a retirement account could potentially “cannibalize” some 199A deduction. But, it could also be a good thing. It’d be a good thing if you’d otherwise bust the high earner threshold of $207.5k/$415k and you don’t pay employee wages and don’t have depreciable assets, or you’re an SSTB. Because then you’d lose 199A entirely, so reducing QBI by squirreling it away into a retirement account could help you come back down below the threshold so you can at least get some deduction back. OTOH, it could also potentially be a bad thing if your QBI is already modest (not over threshold), because it may lower the base against which the 20% deduction is applied. This interplay between 199A vs. small biz retirement accounts can get nuanced, so what you really have to do is just “run the numbers.” Stephen Nelson has a good post on how retirement plans impact 199A, and another post on ways to think about retirement strategy in light of 199A.

2. Entertainment expense deduction eliminated. Pre-Trump, you could deduct 50% of “entertainment” expenses if they were actually business-related, like entertaining business clients. Under Trump’s tax bill, you can no longer deduct “an activity generally considered to be entertainment, amusement, or recreation” even if business-related. However, you can still deduct 50% of business meals.

3. Moving expense deduction eliminated. Previously you could deduct moving expenses when certain distance criteria were met. Trump’s tax bill eliminates this deduction entirely (unless you’re in the military).

Breakdown of how the Trump tax bill works: estate planning and 529 plans

1. Estate tax exemption doubled. Pre-Trump, the estate tax exemption was $5.49M per person (doubled for married couples). Trump’s tax bill doubled these amounts, so for 2018 it’s $11.2M and for 2019 it’s $11.4M (again, doubled for married couples). This basically helps super rich people gift even larger inheritances without paying estate taxes. Even before Trump, the estate tax only applied to fewer than 5k estates per year, dropping 95% since 2001. So Trump’s increase of the exemption ceiling makes estate tax planning even less relevant now. On the flipside, it means the IRS will more easily audit every single estate subject to the estate tax and spot abuses.

2. 529 plans can now be used to fund private K-12 schools. The big change here is you can now use 529s to pay for K-12 private school (but limited to $10k per student per year), whereas before you could only use it to pay for college. Before, you had to choose between whether to fund K-12 using Coverdells vs. fund college using a 529. The new 529 rules make 529s more attractive because they can now be used for either.

Conclusion

Well, there you have it. The key Trump tax bill changes that impact W-2 income, investment income, real estate income, and side hustle/business income.

For wealth hackers and early retirees, there are some nice new benefits:

- Lower tax rates, bigger standard deduction (but no personal exemptions)

- New 199A deduction if you’re running a side biz

Importantly, however, Roth IRA recharacterizations are now poof-gone.

Other tax code changes only start to apply the more income you have, the more investment real estate you have, etc.

Note: In writing this post, I learned a lot from Michael Kitces’ analysis of the bill and recommend it if you’d like even more detail.

Related: Using what you learned in this post, be sure to also check out our related post on tax loss harvesting and tax gain harvesting.

Discussion: How will the new tax changes impact you? Any big surprises? Do you think it makes sense to change your / your business’s filing status to take advantage of 199A? Leave a comment below!

Leave a Reply