Which retirement account is better: a traditional tax-deferred account or a Roth account?

A lot of advisors say: “it depends.”

They’ll say, if you believe taxes will be higher now than later, then contribute to a traditional account and get tax deductions now. If you believe taxes will be higher in the future, contribute to a Roth, take the tax hit now, then enjoy tax-free withdrawals later.

Whether taxes are higher now vs. later, of course, has a lot to do with how much you earn now vs. how much you expect to earn later / in retirement, plus what tax rates are now vs. what you expect them to be in the future.

Well, this is a false choice.

Today I’m gonna show you that contributing to a traditional account upfront is ALWAYS superior for nearly all taxpayers, especially those who plan like I do to retire early.

The key is this: after contributing to a traditional upfront, you then slowly convert to a Roth IRA AFTER you retire. This is called a Roth ladder and it lets you get the best of both worlds. It means you avoid taxes on money going in, avoid taxes on growth, avoid taxes on conversion (if done right), and again avoid taxes on withdrawal.

In tax planning, a completely tax-free pass-through like this is the holy grail.

Why you should care about this at all

For most workers, taxes are your single biggest expense. You may not notice it because they get withheld from your paycheck. But when you look at the size of your tax withholdings, you see they dwarf all other expenses — including housing.

Taxes comprise more than ONE-THIRD of my gross income, and no other expense comes close.

That’s why it’s super important to do efficient tax planning. And tax-advantaged retirement accounts are a key strategy for achieving this.

In fact, the strategy I’m gonna show you is one of the rare few that’s universally true for nearly everyone. Plus, it snowballs over time: follow this strategy early in life and you WILL accelerate your retirement by YEARS.

Quick recap on the different types of tax-advantaged accounts

When I talk about tax-advantaged accounts, I’m talking about them in a generic sense.

“Traditional” simply means funding with pre-tax dollars and deferring all taxes until you withdraw. Investments grow tax-free, but they get taxed entirely as ordinary income upon withdrawal.

“Roth” simply means funding with post-tax dollars, but everything is tax-free thereafter.

Both traditional and Roth accounts come in different types, such as:

Traditional:

- IRAs

- 401(k) Plans for company employees

- 403(b) Plans for teachers

- 457(b) Plans for state and local government and non-profit employees

- Thrift Savings Plans for federal government employees

- Simplified Employee Pension Plan (SEP)

- SIMPLE IRAs

Roth:

- Roth IRAs

- Roth 401(k) Plans

- Roth 403(b) Plans

- Roth 457(b) Plans

- Roth Thrift Savings Plans

It doesn’t matter which type you have. What matters for tax planning is which bucket — traditional or Roth — it falls into.

How this strategy works

We mentioned above that traditional wisdom says if your taxes are higher now, go with a traditional account; if your taxes will be higher in the future, choose a Roth.

Let’s take a look at how a traditional is always mathematically better when you have earned income, especially if you plan to retire early.

Step 1: Contribute pre-tax to a traditional account during your working years

First, if you can afford it, I strongly recommend maxing out your traditional contribution every year. Currently the max annual contribution is $22,500 ($6,500 for IRAs).

To fund $22,500 in your account, you’ll need $22,500 of earned income, which you’ll deduct from your paycheck and you won’t pay taxes on that.

To fund $22,500 in a Roth, you’d need as much as $35,714 of earned income (if you’re at the 37% marginal bracket), since you’re using after-tax dollars.

This means you literally end up with more dollars in your pocket when you choose a traditional over a Roth.

In fact, if you earn $100,000 income, you’d have ~5% more dollars (based on 2023 tax brackets) in your pocket at the end of the day, shown here:

Traditional…

$100,000: income

(22,500): 401k contribution

(13,850): standard deduction

63,650: taxable income

(7,198): taxes

(0): Roth contribution

$56,452: net income

Roth…

$100,000: income

(0): traditional contribution

(13,850): standard deduction

86,150: taxable income

(9,898): taxes

(22,500): Roth 401k contribution

$53,752: net income

(This assumes you’re a single filer.)

The extra dollars you save by shielding contributions from taxes upfront can now be reinvested in a regular, taxable account.

If you do this every year, your taxable account will grow much faster than someone who is only contributing to Roth. Over many years of compounding, this gap will get big. We’ll show you how big in a second.

Step 2: Do a “Roth ladder” once you retire to withdraw conversions tax-free

Maybe you’re thinking, “Hey, all well and good, but now you owe taxes on the traditional when you withdraw…”

Nope.

The year after you retire (hopefully early), you’re gonna start doing a Roth conversion ladder. A Roth ladder is a technique where you convert a little bit each year from your traditional account to your Roth IRA.

How much to convert? Well, conversions are taxable events. But if you convert up to the standard deduction ($27,700 MFJ, half for single filers), then you can move that money into your Roth IRA and pay zero taxes.

Moreover, unlike Roth IRA contributions, which are capped at $6,500 and subject to income limit phaseouts, Roth IRA conversions have no cap and no income limits. Win.

Now, the rules have always let you withdraw original contributions to a Roth IRA tax-free and penalty-free. But when you do a Roth conversion, there’s a twist: you have to wait 5 years before you can withdraw those original contributions.

That’s where the “ladder” comes in.

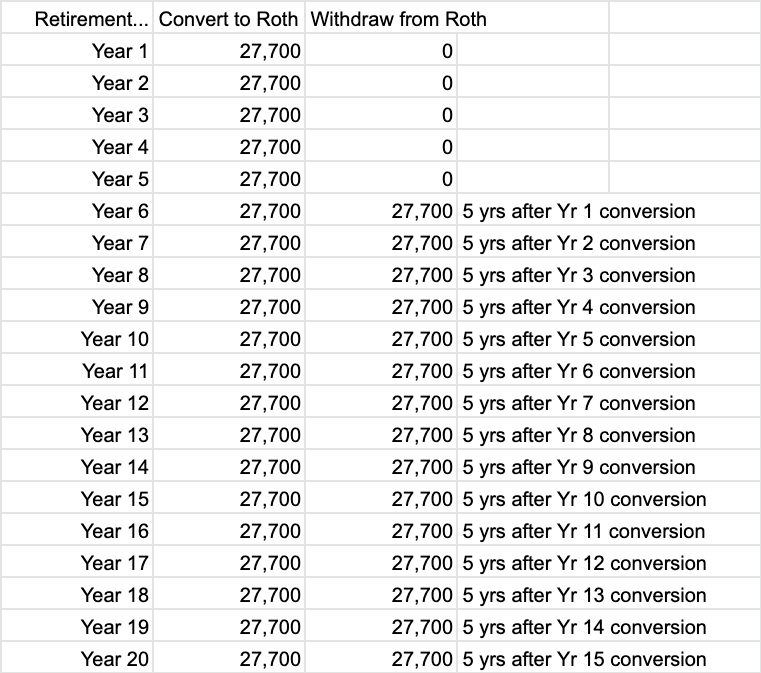

You can structure your conversions and withdrawals like this:

Each year you convert an amount exactly equal to the standard deduction. Five years later, you start withdrawing those contributions tax-free.

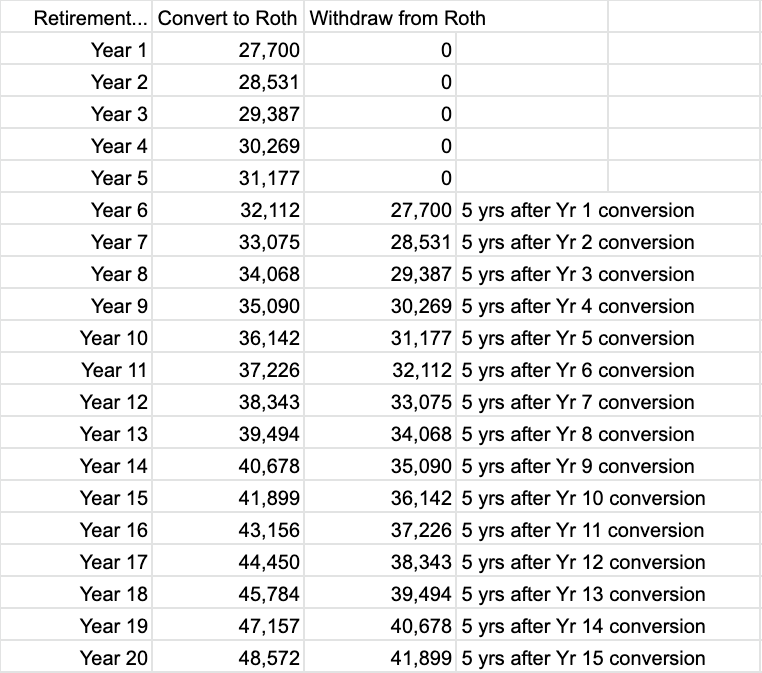

But wait, the IRS actually increases the standard deduction each year to account for inflation.

If inflation is, say, 2.5% per year on average, our Roth ladder will actually look something like this:

Step 3: Cover your first 5 years of expenses from other sources

Because the Roth ladder has a 5-year waiting period, you’ll have to cover your expenses for the first 5 years from other sources.

You can cover your expenses with:

- Unemployment benefits

- Withdrawing prior original Roth contributions tax-free and penalty-free

- Rental income

- Side hustle income

- Dividend income from your taxable account

The last one is especially attractive, because qualified dividends and long-term capital gains (up to $89,250) are taxed at zero.

So, theoretically, you could live off $89,250 tax-free dividend income or long-term capital gains, and convert $27,700 tax-free to Roth every year (adjusted annually for inflation).

Five years after starting your ladder, you can then begin withdrawing your ladder conversions tax-free. (Any earnings, however, must stay in the Roth until you’re 59.5.)

This means you enjoyed:

- Tax-free contributions

- Tax-free growth

- Tax-free conversion to Roth

- Tax-free withdrawals

Putting it all together

So, the strategy is to:

- Contribute the max $22,500 to a traditional account every year until you stop working

- Once you retire, convert the standard deduction amount each year to Roth

- Live off other spending sources for the first 5 years; qualified dividends and long-term capital gains taxed at zero if under $89,250

- If you earn any ordinary income during early retirement, which is a real possibility (e.g., rental income or side hustles), make traditional contributions with it to shield against taxes…eventually that money will get laddered into Roth anyway

- After 5 years, start withdrawing Roth ladder contributions tax-free and penalty-free

- Pay zero taxes on everything

So…what’s the result of all this?

Results after 30 years

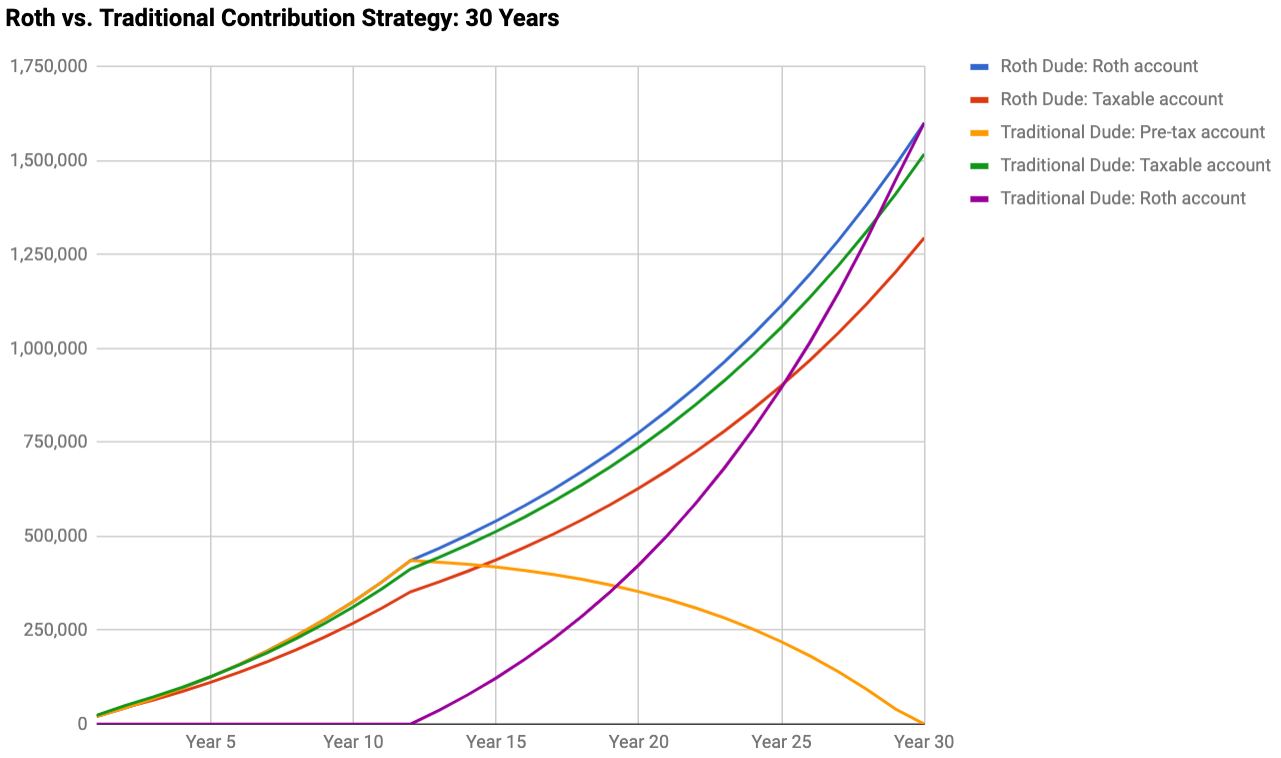

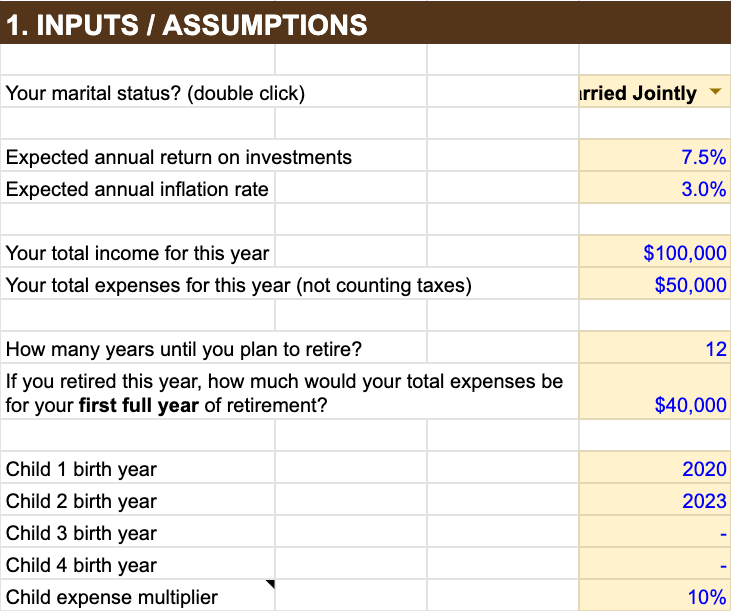

Let’s say you and your spouse currently earn a combined $100,000 and you want to retire in 12 years. Assuming you plan to have 2 kids and you max out your retirement accounts every year, the gap becomes significant after 30 years:

In fact, using these assumptions:

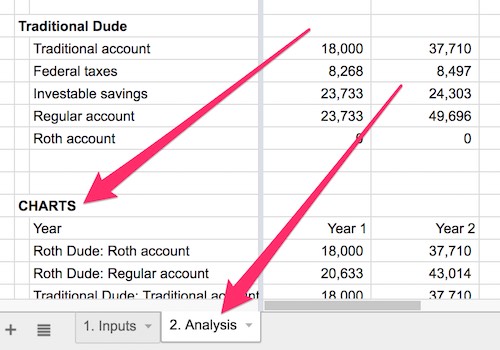

…after 30 years both traditional and Roth dudes have the same amounts in their tax-advantaged accounts, but the traditional dude has $235k more in his regular, taxable account than the Roth dude has in his.

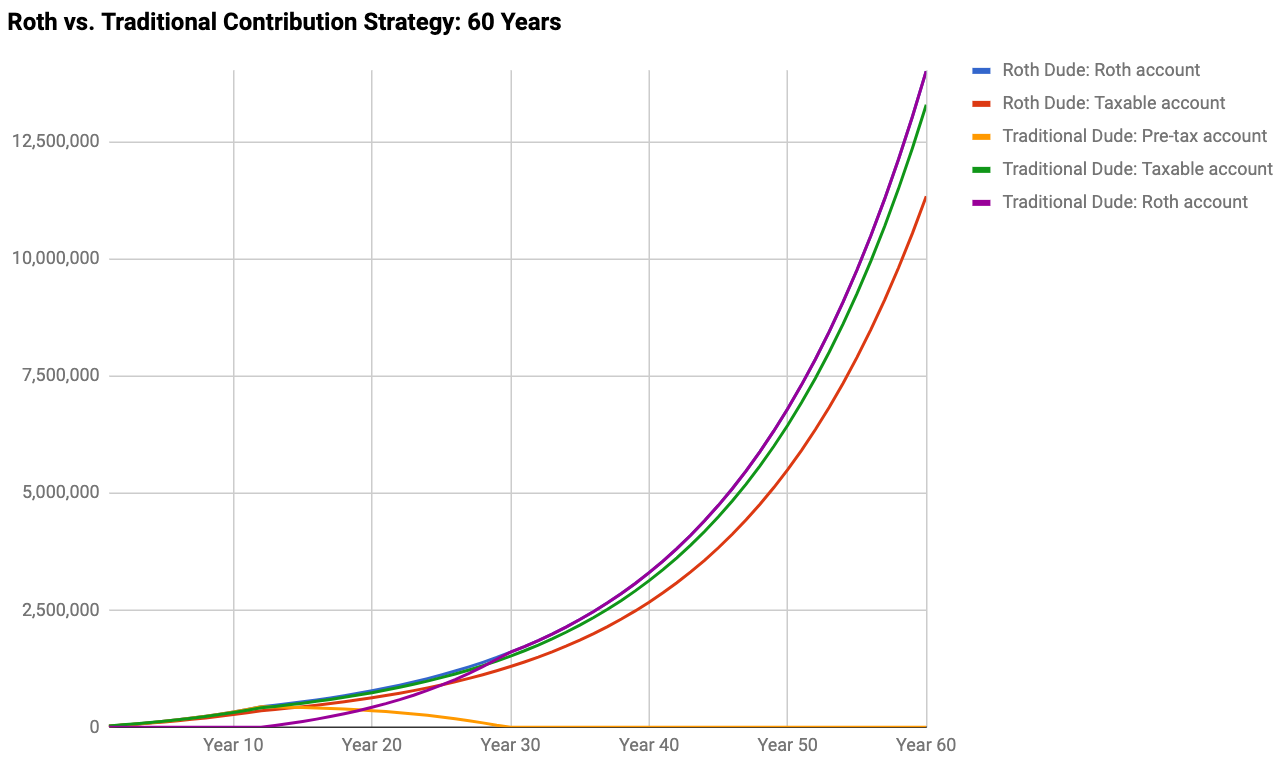

Results after 60 years

Across a lifetime, the gap becomes REALLY big.

At 60 years, the traditional dude has >$2M more in his taxable account than the Roth dude:

That, my friends, is because of the magic of compounding.

Now it’s your turn

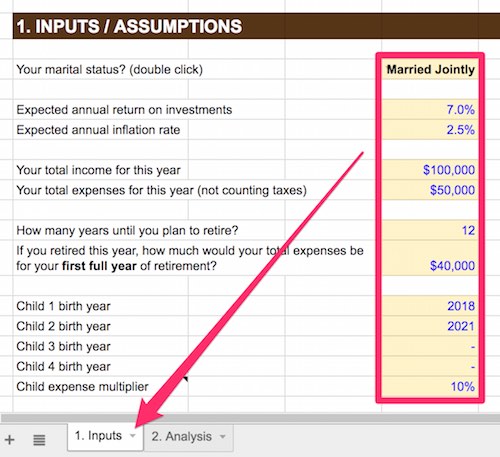

Try it for yourself.

First grab the spreadsheet:

Next, punch in your assumptions on the “Inputs” tab.

Then switch over to the “Analysis” tab to check out the charts.

You can see the exact dollar gap in the “Analysis” tab, too, in column AG labeled “Year 30” and column BK labeled “Year 60.”

More reasons to convert to Roth

If the tax advantages alone weren’t enough to convince you about the benefits of contributing traditional then laddering to Roth, maybe a few other considerations will…

First, while both accounts let you withdraw penalty free when you turn 59.5, traditional accounts REQUIRE you to start withdrawing at 73, whether you need to or not.

Roth IRAs don’t have such a requirement. You can keep your Roth money in the account as long as you want, and even bequeath it to heirs when you die. So, aside from taxes, there is no deadline for when you have to withdraw. And what if you converted to a Roth 401k (which does have RMDs)? No problem, just roll that out to a Roth IRA and then there’ll be no deadline.

Plus, remember you can always withdraw original contributions from a Roth tax-free and penalty-free. (You just can’t take out earnings.) Not so with a traditional account. The only exceptions are:

- paying college expenses for you or a family member

- medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of AGI if you’re 65 or older or 10% of AGI if you’re younger than that

- buying a home for the first time (limited to $10k withdrawal)

- paying for a sudden disability

With a Roth, you can even take out earnings penalty-free and tax-free before 59.5 for disability or a first-time home purchase, assuming you’ve had your Roth open for 5 years. But you only get penalty-free (not tax-free) earnings withdrawal for medical or college expenses. Note: Pre-59.5 Roth earnings withdrawal rules can get nuanced, so talk to an advisor if you really need to understand them.

Does the Roth IRA conversion strategy work for non-IRA accounts like 401(k)s?

Yes, but with the extra step mentioned above: either convert to Roth 401k and then roll over to Roth IRA, or roll over to traditional IRA first and then convert to Roth IRA. You can’t convert directly from traditional 401k to Roth IRA.

Final thoughts

So, we’ve seen that the key strategy of a Roth ladder is making traditional contributions upfront, then reinvesting the extra dollars in a taxable account.

This puts more dollars to work for you without you working any harder or earning any more, simply by keeping those dollars out of Uncle Sam’s hands.

So, my recommendation is: never contribute to a Roth upfront.

If you have ANY earned income, do yourself a favor and contribute to a traditional first, then convert to Roth once your circumstances are tax-favorable.

Be sure to also check out my podcast episode on building wealth using a Roth ladder.

Discussion: Have you used this strategy before? Any interesting twists or variations you’ve found? Leave a comment and let me know!

I will not be a candidate for FIRE. Retiring next year at age 69 and starting SS along with my wife FRA at 67. Our combined SS income is projected at $61,212. IRA balance = $280K and Roth IRA = $240K. Our expenses are expected to be less than SS therefore, all IRA decisions are made toward efficiently growing for legacy distribution unless we have unforeseen medical needs. Do you have suggestions of how to tax efficiently perform partial Roth conversions each year to minimize eventual RMDs which will be driving more of our SS benefit into taxable income status? Provisional or Combined income calculations are difficult to project. We will have no other income other than SS and RMDs. Thoughts are to wait on the first year of SS and have a CPA file taxes. We would like to convert but, it seems any conversion will force 85% of our Social Security to be taxable income. Possibly, we could only convert $8-10K each year. This seems to eliminate the advantage of converting. Any thoughts are appreciated.

Hey Andrew!

Thanks for all your help on these topics.

I’m still conflicted on this question of Traditional vs Roth, especially for IRA’s. After listening to your related podcast and reading your related post, I Googled around a bit to see other opinions. I was hoping to get your opinion on two items I found.

One item is the income limit for tax deductible contributions to a Traditional IRA. I would be ineligible to claim a tax deduction for Traditional IRA contributions (due to income), but I am still eligible for Roth IRA contributions 100% up to the limit. The lack of Traditional IRA tax deductions and my inevitable barring of allowed contributions to a Roth IRA over time (as my income surpasses the allowed threshold within ~5 years) makes Roth IRA contributions more appealing at the moment.

The other item is related to the first. This is the matter of tax law and changing legislation. Supposedly the back door strategy has a target on its back with recent proposed bills and I am worried that the strategy will no longer be around by the time I can start to take advantage of it (~25-30 years).

The current recommendation seems to be based on the current state of law around the back door strategy. Does the recommendation change if benefits of the strategy are reduced or eliminated completely? Do you think this is likely to happen?

Thanks again,

Rylan

>> The lack of Traditional IRA tax deductions and my inevitable barring of allowed contributions to a Roth IRA over time (as my income surpasses the allowed threshold within ~5 years) makes Roth IRA contributions more appealing at the moment.

In this scenario you don’t even have a choice – you have to contribute to your Roth, you don’t even need to do the backdoor method then. So there’s not even a choice to make here.

If the backdoor Roth strategy is nullified by congressional legislation, then of course the recommendation will change – it won’t even be valid anymore in that case. So far, that has not happened. Who knows if it will happen, but it probably won’t happen in 2022 anymore, so might as well take advantage of it now if you’re able to.

This is the first article I’ve read that has revealed in full what my wife and I are actually doing already. We have been successful with it completely with no downsides.

I retired at 54, my wife at 51. Before going full plunge, I did continue to work a simple part-time job to keep income flowing until the numbers made perfect sense as being true. Coming into this, we had already lived debt-free for two decades. We also paid for our newly built house with cash in 2013. So, there was absolutely no debt and the house was bought basically at the bottom of the housing market in a brand new neighborhood to boot just outside of town. We had rented entirely before that while building our savings. Long long ago, we had owned a couple houses in another State during our debt-filled lives. Medical issues with one of our two kids cost us everything way back then. It’s what opened our eyes to life’s unfortunate surprises and having heavy debt with no savings. Once debt-free, we never turned back.

Anyway, let’s talk about now. Three buckets, no debt, own house free and clear, retired early:

Taxable bucket: Lots of cash and dividend stocks throwing off about $5k/year in tax-free dividends. Stock is there to cash out in a big emergency, but even that would be long-term capital gains. The rest of that account is simple pure cash. Drawing on that cash obviously generates no income or tax consequences. There is enough cash to live on until 59.5 years old. Expenses are only $25k/year. Yes, you read that right. Sounds very low until you consider that zero taxes are being paid. No rent or house payments. No car payment. No debts at all. Don’t have to drive my car to work each day, so gas expenses are low. Everything we need is within minutes of our house. Then, consider we live in Wisconsin. You’d be thinking, ouch…that’s a high tax State. But is it? While property tax would seem high relative to cost of house, the housing itself is priced much lower than many States. Then, consider that the State tax rate is a sliding scale and I’m getting it all back. Then, here comes the hidden winner in Wisconsin: Usually food costs occupy a large amount of retirement expense. Wisconsin doesn’t charge tax on food. That’s a big one. We have a Walmart 5 minutes from my house. Since we have a Walmart credit card with 5% off all purchases, including groceries and curb side pickup, we save even more on food costs. Obviously, we pay off credit in full each month to avoid interest payments.

Roll-over IRA bucket(s): In order to satisfy ACA health insurance requirements, we need to show income. That’s where the Roth conversions kick in. We combine the Roth conversion with the dividends paying out of the taxable account to “program” our yearly income. Using the ACA calculators we can figure out how much to convert each year and not go over the amount that would generate a monthly insurance cost. We can push $40k/year “income” at this moment in time, and the credits basically cover all the insurance for my wife and I. Before anyone has a hissy-fit with doing that, be aware that the government’s own website encourages early retirees specifically to use ACA. It’s a specific benefit that they want early retirees to take advantage of while they are transitioning to Medicare later on at 65 years old. We wish we did not have to take Medicare at 65.

Roth bucket(s): My wife and I already had established Roth accounts many years ago and had funded them. So, there are plenty of funds in them already that have 5 years accumulated time to meet withdrawal requirements. The Roth conversions are in-process before we reach 59.5 as well.

Another important change we are making is pushing Social Security off to 70. This maximizes our Social Security, which we really don’t need during our 60’s. More importantly, this gives us more time to get funds transferred out of our traditional roll-overs and not trip up SS taxes.

The health advantages of retiring in our 50’s have been huge. We have both lost large amounts of weight, eat healthy, sleep well, stress is so low and we don’t beat our bodies up. My weight is where it was back in high-school! BMI is perfectly centered. Can’t remember seeing myself look so fit. Combine this with being in my 50’s means able to do so much NOW, and reduce probabilities of bad health in the later years.

So, we basically “program” our yearly “income” for taxes and ACA purposes. The Standard Deduction gobbles up most of the conversion as tax-free (~$25k). We are taxed at 10% for a small remaining part of the conversion (~$10k). The dividends are tax-free (~$5k). The ACA is free at this level. No State/Federal/FICA income taxes to pay. We live off of actual dividends/cash until 59.5. The food is tax-free. Property tax is reasonable ($3700/yr).

Hope I didn’t miss anything. It works. It’s real. Look forward to discussion and/or feedback…

Thanks for sharing this Steven. You’re living the dream. Glad to hear you learned how to hack your retirement at a relatively young age – the results clearly speak for themselves, since you’re now able to enjoy stress-free, low/no-tax retirement!

You’re crushing it StepenK1. Congratulations!

There is value in having money in taxable, tax deferred & tax exempt. If you build a retirement plan on current tax law but retirement is 30 years away, you may find your personal circumstance or tax laws are different than you anticipated. The challenges I see with this approach.

1) The income from the first 5 years has to come from somewhere. If you assume from your taxable account, you may have to sell in a down market or you have to deal with cap gains before you retire to position your portfolio to safer investments.

2) As mentioned above, if you plan to get the Obamacare premium discount you have to manage your MAGI below the 400% Federal Poverty Level threshold at a minimum. MAGI is calculated before any deductions. So the funds being converted to Roth count towards the threshold. Having money already in a Roth account is crucial to meeting your income needs without jeopardizing the MAGI threshold. The Roth being tax exempt also allows you to orient the account to produce income before retirement without generating taxes. (There is an exemption to the MAGI cliff in 2021/2022 and some lawmakers want to make this permanent … if so there is it basically becomes an 8% tax toward your premium).

3) Consider other income sources such as rental income, royalties, deferred compensation, restricted stock vesting, stock options, pensions & Social Security. The standard deduction isn’t really available to make the Roth conversion without tax consequences for many people.

4) If you do traditional 401k/IRA contributions only your entire career, you likely have a balance so large you will never be able to convert all of it to Roth tax free. You will pay tax on the RMD and possibly additional Medicare Part B premiums and other inventions congress comes up with to means test benefits.

David, you raise good points. It’s true, this strategy might not be the right fit for everyone. But for many, it will. There are also ways to mitigate some of the risks you identified.

For example, you need spending money for the first 5 years, but if you plan early enough around it and amortize it in the years leading up to retirement/FIRE, you could have your 5 years of expenses ready to go by the time you pull the trigger. That money could be a laddered bond portfolio that matures a year’s worth of spend each year.

You could also live for a few years in a lower cost foreign country during the first few years of retirement when you’re relatively young, have more energy and interest in traveling, and that could drastically reduce the amount of money needed during the first 5 years in the first place.

Also if you go abroad, you might be able to get really good quality healthcare for cheaper than Obamacare, even if you pay out of pocket, because many countries have more affordable healthcare than the US. If you stay in the US, the 400% FPL threshold is indeed a real obstacle, if you absolutely must get Obamacare + the subsidy at the same time.

If you have a rental property, you might have enough depreciation expense to zero out your income, even though you’re still collecting cash flow – no tax on that. (If you’re mortgage is already paid off, this may be harder.) With stock, you can take out a portfolio loan if you need spending money without incurring any taxes, capital gains, or triggering any MAGI thresholds.

You don’t have to convert the entire 401k balance to Roth to benefit, either. Even if you convert only a fraction, it’s a fraction that entirely escaped taxation that would not have otherwise been able to do so had you contributed directly into a Roth. If you’re able to convert half your 401k balance, then spend the other half during the first years of retirement when your tax rate is super low, and before RMDs kick in, then you’ve still enjoyed some serious tax breaks / arbitrage that would not have been possible had you only been contributing to Roth your entire life.

Thanks Andrew! There are always options. You obviously put a lot of thought into this. The approach of doing Roth conversions is a great approach even if you can’t achieve the zero tax bracket. Any $$ you convert and pay in a lower tax bracket is a win (as long as you have the cash to pay the taxes). My only quibble with the thesis is “it’s always better to do traditional”. I have value for having money in taxable, tax deferred & tax exempt for maximum flexibility.

Yeah it’s not going to be right for every single taxpayer, but I do believe given the flexibility and optionality it provides, compared to taking the tax hit right up front (with a Roth), it will end up being the right choice for *nearly all* taxpayers.

Two questions: 1) I’ve believe that the only reason that you move the Roth 401K to a Roth IRA (after conversion from traditional 401K is to avoid RMDs. True ? 2) If you 401K allows (and you can afford it) is there any reason to not max your pre-tax, traditional 401K ($19,500) and also contribute a max of after-tax dollars ($39,000) for $58,500 total?

1. Avoiding RMDs is one big reason. Another might be because your Roth IRA probably has a wider diversity of investment options to choose from.

2. If you can afford it, there’s no reason…assuming you can convert the after-tax dollars to Roth immediately. If for some reason your plan doesn’t allow for that, then it’s not worth contributing the after-tax dollars.

Should we not max out BOTH the 401k AND the ROTH? I’m already maxing out my 401k. Should I also contribute 6,000 to the Roth?

If you can afford to, yes max out both.

Few other items I forgot to mention. If during time of unemployment, you expect your income to go to zero thus giving more opportunity to convert at 0% tax bracket, think again. Most people qualify for unemployment which may keep you in a tax bracket. If you have a spouse, one spouse may still be working. If you don’t have a spouse, the Obamacare premium subsidy loss itself can cause the 0% bracket to turn into a 15% effective tax bracket. Even the 0% qualified dividend is subject to Obamacare premium subsidy loss thus even that is at 15% tax rate which might not be any lower than when you were still working. Relying on qualified dividend tax break does not seem too prudent anyway especially if the rate is 0%. Unlike Roth, where the legislation did make it clear that the reason you are getting this tax break is because you paid tax upfront and agree to certain holding period requirement, the qualified dividend tax break is only based on limiting double taxation of corporate and personal income tax. Use other OECD nation’s tax as a guide and you won’t really find such huge breaks for qualified dividend–they might reduce the rate in half but they don’t typically set it to 0. Many other OECD countries do have tax free retirement savings account so I suspect the Roth will stay but perhaps with some modification in contribution limits, adding RMD, etc. but the odds are rather good it’ll remain tax free because U.S. has tax treaties with many other OECD countries and a tax deferred and tax free retirement account are something they will negotiate for its taxpayer.

This strategy may work for some but not really for the bulk of the population.

1. Most people in the U.S. do not have health coverage after they stop working other than

buying into medicare at age 65. If you leave work earlier than that most people end up

buying health insurance through Obamacare exchange. Obamacare premium subsidy is set

based on your household side and income level under 400% of federal poverty level.

For household of 2 for 48 states and Washigton DC is $65840 in 2019. The loss of subsidy is

approximately 15%. If your combined income goes even a $1 above the $65840, the premium

skyrockets to the market rate as no subsidy is given. Effective, if you were to control

your income to below this amount to say $65000, you still lost $9750 in healthcare subsidy

which effectively another layer of tax. Another way to think about this is even if you

were to deduct your contribution at 22-24%, you can end up paying 12% in tax plus another 15%

for loss subsidy thus your strategy fails because 27% is higher than 22-24%. In fact, even in the situation where you are within the 0% tax bracket isn’t nearly as favorable because the loss of healthcare subsidy alone is worth 15%–there’s no exemption on that part of it. There’s a separate credit in addition to subsidy for those under 200% federal poverty level. Those under 100% federal poverty level can potentially get healthcare through welfare program medicaid.

2. What happens after age 70 1/2? With traditional retirement plans, you are then subject to

required minimum distribution. The RMD as a percentage of balance at the end of the previous year increases each year thus forcing more money to be exposed to income tax even if you didn’t need the money at the moment.

3. What happens if you decide to make a larger purchase like a second house? If you had most of your money in a traditional retirement plan, I suppose you can try to get a loan to spread the tax burden but getting a loan. However, getting a mortgage when you have already stopped working might not be easy. Taking too much money at once pushes youself into a high tax bracket. Roth gives you a lot more flexibility.

4. How much of your social security income becomes taxable is based on 1/2 have your social security income plus other income _excluding_ Roth distribution. The actual tax bracket actually can become a lot higher because of this formula. Tinkering with a tax software will give you a pretty good idea of the tax bracket. Start with an estimated social security income and other income excluding your traditional IRA distribution. Write down the tax due. Then add $1000 in traditional IRA distribution. Then look at the difference. Don’t be surprised if this number is North of $300 indicating effectively, that distribution cost 30% in increased tax.

5. At higher income, medicare part B and drug coverage cost can increase. Right now, it impacts about 4.7% of those paying medicare premium but since they froze inflation indexing for the threshold for many years, it may impact even greater population. For the moment, the effect is about 5% extra cost. So if your tax on your traditional IRA is at 22%, it might actually increase it to 27%. However, as we all know. medicare premium have been going up much faster than inflation thus the 5% extra cost might be 6%, 7%, or maybe even much higher by the time you’re 63. Yes, it isn’t 65 but it is income based on the 2 years prior to when you are paying for medicare.

6. Your assumption is that you remain married in retirement. U.S. has the highest divorce rate in the world. One common divorce timing is just as people are retired or shortly after that. Suddenly, the currently generous marital surplus in the tax bracket turns back into a single filer where brackets are much narrower. Housing is the highest expense for a household budget typically and it doesn’t go anywhere near in half when you live alone. Therefore, your need to withdrawal from the retirement plan didn’t go down in half but much of your tax bracket and deduction did go down in half. The result is that you pay more tax. Ok, suppose you didn’t get

divorced. People still can die even if they were healthy. Bad things can happen such as getting into an auto accident.

7. Some people still get a pension. 1/4 of the U.S. workers work for one form of government or another. Most of them do get a pension other than social security. It is another form of tax deferred income. Thus their tax bracket might not be as low as you would suspect. In the private sector, those working for financial services often still get traditional pension as well.

8. The example you gave of being in the highest tax bracket is flawed because those people most often max out all retirement plans and they still have money left over to invest in a taxable account. They end up in a situation with not enough tax shelter that is cost effective. In the end, they end up not needing to withdrawal from the retirement plan but if they had done mostly traditional IRA, they must take at least the requirement minimum distribution which becomes taxable. Had they gone the Roth route, the money can keep growing tax free for their lifetime and their surviving spouse’s lifetime. After both spouse demise, the non spouse heir must take a required distribution over their lifetime on the Roth account but at least it will be tax free. This non spouse heir might still be working so having it is a Roth might be a much better thing to leave behind than a tax deferred retirement account.

9. The more you accumulate, the more likely your bracket will be at least as high as your working years as during your retirement year. I already explained that the low tax bracket is a myth in too many cases because of Obamacare premium subsidy and tax formula for social security, and premium adjustment for medicare. But even without those items, there’s only so much retirement income you can distribute in the lower bracket within your lifetime especially with

required minimum distribution causing a forced distribution. The low tax bracket is only so wide and in that tax bracket, the effects of Obamacare and social security tax formala often negates or even reverses its benefits. With RMD’s, you typically end up with more money than you need and you end up investing the excess to a taxable account that generates taxable earning. The spiral of increasing tax bracket becomes never ending.

So whom might the traditional IRA still work? I suppose if you are a military retiree with health benefits, you don’t have to worry about Obamacare. But the other factors still can apply to the military retiree. People’s situation change over time. Someone whom never originally planned their career might end up working for a local government later in life thus their early plan of contributing to the traditional might backfire at that point. Let’s say a person did do this and

they joined local government at age 40. By this time, there might be a substantial balance in their 401(k) plan from private sector work making it harder to convert to a Roth in a tax efficient manner. The longer you let it grow, the harder it is to convert at a lower bracket and combined with pension distribution and RMD, it’ll become even harder. So the easiest way to deal with it is as soon as you can.

Some people think that if they temporary lose their job, they can convert to a Roth at that time. That may work for small balance when you are still young and health insurance premium is still low. But as you accumulate more in the retirement plan and your premiums increase, the issue with Obamacare becomes a new problem. COBRA only allows continuing coverage from employer by paying the full value of the group insurance plus some administrative cost for 18 months–the total cost typically winds up being higher than buying health insurance from Obamacare especially for those under 50.

The idea of early retirement is nothing new. It is only that the internet actually made it more public with an acronym like FIRE movement. Reality is that there are many traps and people have historically not really completely retired or returned to work after they left their primary job at an early age. So their tax bracket simply didn’t go down nearly as much as they expected from the various traps I mentioned plus their own change of plans. People simply do not know if they really want to retire until they get to the age they planned even if the numbers made it possible to do so.

Roths are also great for putting away found money. We sold my mother-in-laws house that we inherited after doing some repairs and used the proceeds to max out the Roths for two consecutive years before the April 15 deadline (plus a trip to Hawaii and new leather couches). $26K just that easy. Some side hustle cash from mowing lawns or part time endeavors can go straight to the Roth especially if you have expenses like transportation and phones you can write off against the earnings for tax free Roth contributions.

I can’t find this idea anywhere, and i’m wondering if you could “hack” the system in another way. For example contribute to Roth IRA max of $6500 at the beginning of the year so that you gain the growth/interested/dividends (lets say 10% for ease of round numbers, so $650 in growth which would then continue to grow tax free) and then withdraw the initial contribution of $6500 to then use that money to fully fund the traditional and get the tax advantage for that same year??

The concept would be to grow the roth in interest/dividends which would grow tax free for retirement while also getting the tax advantage now from the traditional. Obviously would want to do the conversion latter later if possible, but say that never happens due to continuing to work through older age, would this be an alternative option to have roth and traditional growth?

Has anyone done this or know the rules as to if this is possible.

thanks in advance

Hey CJ, you could do this and it would “work” but it wouldn’t be my strategy. It’s risky, exposes you to short-term price fluctuations (and trading fees), and the upside seems limited for the amount of work involved.

The way you’d do it is:

1. Make a Roth contribution at the start of the year, say Jan 1.

2. Invest it in stocks and see if it grows throughout the year.

3. On or before April 15 of the next year, liquidate the stock so you can withdraw the original Roth contribution in cash and put it into an IRA.

4. Attribute the IRA to the prior year and take the tax deduction on your tax return.

5. The money will sit in the IRA thereafter (you can buy the stock again once it’s inside the IRA – make sure you don’t run into the wash sale rule if you sold at a loss).

6. If you realized capital gain in the Roth, you can continue to let it compound.

7. Rinse and repeat.

In the best case scenario, doing this over and over could result in a little bit of Roth gain each year before you transfer funds back into your regular IRA.

However, there’s also a risk you lose money and there are a few reasons why I probably wouldn’t use this strategy. The main reason is it exposes you to market timing and therefore seems unduly risky. The market generally moves up over long periods of time, but can languish in any given year (or even year to year). This strategy presumes the market will move up every year — if it didn’t, you wouldn’t do this strategy. Actually, it presumes the stock price on April 15 (or whenever you liquidate) is necessarily higher than the price on Jan. 1 when you originally buy. You’re taking a risk that you’ve got the timing right…on both ends. What if the market tanked in a given year, like in 2001, 2008, or early 2016? And what if it meandered nowhere over a period of several years? Come April 15, you might have a hard choice to make: cut your losses, liquidate, and transfer to IRA (potentially less than the max contribution given your losses)? Or keep it in your Roth, don’t liquidate, but lose the IRA tax deduction? Buying and liquidating (with long holding periods in between) is investing, but trying to time the market every year seems like speculating.

Second, this strategy will involve excessive trading fees and commissions, since you’ll have more trading activity in your account. Maybe this isn’t a big deal for you, but your max contribution is already capped at a few thousand annually, so the trading commissions — both at entry and exit — aren’t trivial in relative terms.

Third, it’s a fair amount of work to execute the instructions / withdrawals / transfers / wait for funds to settle each time you buy / liquidate / transfer. Sure, it’s easy to put a reminder on your calendar each year, but if for some reason your plans change (e.g., the stock price isn’t where you’d like it to be on the day you planned to buy or sell), then you’ll spend time monitoring the market until you are ready to buy / sell. (Again, this gets into speculation territory.)

Also, keep in mind that once your income exceeds the IRA tax deductibility phase-out, this whole strategy goes out the window anyway, since you won’t be able to claim an IRA tax deduction. It also probably won’t work with an employer 401k because the tax deduction is applied directly on each paycheck, not at the time of tax filing on April 15. This means you have to make your Roth 401k vs. regular 401k election in advance. I’m not sure it’s straightforward to recharacterize a Roth 401k contribution and get the money back, only to turn around and deposit it into your 401k instead. I haven’t seen such options in any of my past 401ks.

Thanks for the post.

I’m very interested in your thinking, because I find ‘working the system’ to be a fascinating and enjoyable use of time.

Here’s what I don’t understand: viewed in isolation, this looks like contributing tax-free, and then converting tax-free. But the conversion is only tax-free because you are using the deduction/exemption of $20.7k. However, the tax-free value of the deduction/exemption is fungible, and if you have more than $20.7k in earned income, then you would be forgoing one tax for another, right? Sure this would work if you have no taxable income, but I don’t see that as being very likely.

Also a credit card hint – double up on your Sapphire point bonuses (boni?) by opening business accounts for you and your wife.

Again, thanks for the posts. I watch with interest.

Hey Hawk, thanks for your comment.

It is true the conversion is only tax-free because you’re using the deduction / exemption, and that deduction / exemption is “fungible.” So, if you earn more than this threshold, you won’t be able to avoid taxation — you either pay it from one set of income or another.

This strategy is meant to work for people who have no other source of “earned” income, which in retirement — especially early retirement, years before social security kicks in — is possible, even likely. After all, unless you have rental or side business income, what would be the source of earned income post-retirement? Qualified dividends and capital gains don’t count because they are not considered “earned” income and they are therefore subject to different tax treatment entirely.

So, the idea is: live off your qual dividends and cap gains which get taxed zero at much higher levels, and then use your earned income “allowance” to transfer dollars from traditional to Roth. The transferred dollars ARE technically taxed; they are just taxed zero.

Lastly, even if you have some random income in a given year that would bust you above the deduction / exemption amount, you can always reduce your Roth ladder amount or even “pause” it for a year before resuming the next year when your one-off income goes away. Early retirees will have many years to finish transferring all traditional dollars into Roth, and there’s nothing that says it must be done continuously year after year.

Re: the “double up” credit card strategy – yes, that’s definitely a way to accelerate points faster!

Let’s think about this retire before Social Security and delay converting to Roth IRA until you actually stop working and live off of qualified dividends. Exactly how early are you thinking? I suppose you can try this at age 65 and delay Social Security until 70. That gives you a lousy 5 years to convert. If your balance is high enough, that isn’t going to be easy to keep it at 0%. Once Social Security starts, how much of that income becomes taxable will depend on how much you’re converting and the rest of your other income. If you retire any earlier, most people have to be concerned about how Obamacare credits gets reduced or eliminated as you raised your income from conversion to the point that the conversion cost. So this isn’t a zero cost item and the longer you stretch it out, the more risk you are taking because you don’t have a stable source of income and that many years of inflation on just meeting normal needs like health insurance, housing, food, and energy. Dividends can be cut off, stock market can decline more than 70% and stay low for many years–historically, we had periods it took 15 years to recover after inflation inclusive of dividend based on the U.S. broad market index. Interest rates can stay low so doing this with safer investment/savings won’t do much justice. So to combat those uncertainty, you need an even larger balance be closer to the age you’re going to claim Social Security. That in turn makes it more difficult to keep converting at 0% tax bracket before RMD catches you and before you know it, you’re now paying more for Medicare Part B and Drug coverage because of Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA) and crawling back up to the same or higher tax bracket than when you were contributing the money. Many married couples don’t think they’ll ever get into trouble with IRMAA until one spouse dies and the threshold goes into half. IRMAA just gets worse with rising premiums of Medicare so it is tough to say how much it’ll be when you’re age 65 or older.

The other major flaw is that you’re relying on qualified dividends to be taxed at 0%. That isn’t something you can take for granted and is much easier to change than say taking away the tax free benefit of a Roth.

So no, I don’t think this is a good strategy given the situation with so many stealth tax from Obamacare, IRMAA, Social Security, and even income related property tax breaks for seniors. Politicians will come up with new items to tie to the adjusted gross income all the time. Look at the stimulus check for COVID. It’s income based. If you converted earlier, the money you paid presumably from your taxable account is gone so it isn’t going to generate visible dividends that impact eligibility for such item. The benefits is hidden with the fact that the Roth can grow as long as you live tax free for as high of a balance it can reach. The longer you put it off, the harder it is to keep converting at a lower effective cost bracket (tax plus any stealth tax like increase in health insurance premium, tax on Social Security income, COVID relief or any other random items that the politicians will add) because a larger balance needs many years to convert.

Instead, consider converting earlier even while working if possible to keep your traditional balance low enough to convert within the age 65 to 72 range without falling into IRMAA. If you’ve done well with investing both inside and outside the retirement accounts, maybe the balance you want in the traditional will actually be zero.

There’s also the gift/estate tax aspect of it. $1 in a traditional retirement account is taxable just as much as a $1 in a Roth account. With SECURE Act, most non-spouse heirs aren’t eligible to stretch their inherited retirement account over their lifetime. They have 10 years to take every penny out of those inherited account and be taxed at whatever tax bracket their are in based on their income plus how much they are forced to pull out. Probably best to spread it across 10 years to keep the tax cost down in that case. If they inherited a Roth, it is much simpler, just keep it until the 10th year then take everything out and pay no income tax on it. Since it is in tax shelter longer, it is likely to grow more than the tax deferred inherited account.